Home › Forums › A SECURITY AND NEWS FORUM › 106th anniversary of the Balfour Declaration: Britain’s original sin

- This topic is empty.

-

AuthorPosts

-

2023-11-02 at 16:31 #427330

Nat QuinnKeymaster

Nat QuinnKeymasterThe Balfour Declaration was a public statement issued by the British government in 1917 during the First World War announcing its support for the establishment of a “national home for the Jewish people” in Palestine, then an Ottoman region with a small minority Jewish population. The declaration was contained in a letter dated 2 November 1917 from the United Kingdom’s Foreign Secretary Arthur Balfour to Lord Rothschild, a leader of the British Jewish community, for transmission to the Zionist Federation of Great Britain and Ireland. The text of the declaration was published in the press on 9 November 1917.

Immediately following their declaration of war on the Ottoman Empire in November 1914, the British War Cabinet began to consider the future of Palestine; within two months a memorandum was circulated to the Cabinet by a Zionist Cabinet member, Herbert Samuel, proposing the support of Zionist ambitions in order to enlist the support of Jews in the wider war. A committee was established in April 1915 by British Prime Minister H. H. Asquith to determine their policy towards the Ottoman Empire including Palestine. Asquith, who had favoured post-war reform of the Ottoman Empire, resigned in December 1916; his replacement David Lloyd George favoured partition of the Empire. The first negotiations between the British and the Zionists took place at a conference on 7 February 1917 that included Sir Mark Sykes and the Zionist leadership. Subsequent discussions led to Balfour’s request, on 19 June, that Rothschild and Chaim Weizmann submit a draft of a public declaration. Further drafts were discussed by the British Cabinet during September and October, with input from Zionist and anti-Zionist Jews but with no representation from the local population in Palestine.

By late 1917, in the lead-up to the Balfour Declaration, the wider war had reached a stalemate, with two of Britain’s allies not fully engaged: the United States had yet to suffer a casualty, and the Russians were in the midst of a revolution with Bolsheviks taking over the government. A stalemate in southern Palestine was broken by the Battle of Beersheba on 31 October 1917. The release of the final declaration was authorised on 31 October; the preceding Cabinet discussion had referenced perceived propaganda benefits amongst the worldwide Jewish community for the Allied war effort.

The opening words of the declaration represented the first public expression of support for Zionism by a major political power. The term “national home” had no precedent in international law, and was intentionally vague as to whether a Jewish state was contemplated. The intended boundaries of Palestine were not specified, and the British government later confirmed that the words “in Palestine” meant that the Jewish national home was not intended to cover all of Palestine. The second half of the declaration was added to satisfy opponents of the policy, who had claimed that it would otherwise prejudice the position of the local population of Palestine and encourage antisemitism worldwide by “stamping the Jews as strangers in their native lands”. The declaration called for safeguarding the civil and religious rights for the Palestinian Arabs, who composed the vast majority of the local population, and also the rights and political status of the Jewish communities in other countries outside of Palestine. The British government acknowledged in 1939 that the local population’s wishes and interests should have been taken into account, and recognised in 2017 that the declaration should have called for the protection of the Palestinian Arabs’ political rights.

The declaration had many long-lasting consequences. It greatly increased popular support for Zionism within Jewish communities worldwide, and became a core component of the British Mandate for Palestine, the founding document of Mandatory Palestine. It indirectly led to the emergence of Israel and is considered a principal cause of the ongoing Israeli–Palestinian conflict, often described as the world’s most intractable conflict. Controversy remains over a number of areas, such as whether the declaration contradicted earlier promises the British made to the Sharif of Mecca in the McMahon–Hussein correspondence.

Background

Early British support

“Memorandum to the Protestant Powers of the North of Europe and America”, published in the Colonial Times (Hobart, Tasmania, Australia), in 1841 Early British political support for an increased Jewish presence in the region of Palestine was based upon geopolitical calculations.[1][i] This support began in the early 1840s[3] and was led by Lord Palmerston, following the occupation of Syria and Palestine by separatist Ottoman governor Muhammad Ali of Egypt.[4][5] French influence had grown in Palestine and the wider Middle East, and its role as protector of the Catholic communities began to grow, just as Russian influence had grown as protector of the Eastern Orthodox in the same regions. This left Britain without a sphere of influence,[4] and thus a need to find or create their own regional “protégés”.[6] These political considerations were supported by a sympathetic evangelical Christian sentiment towards the “restoration of the Jews” to Palestine among elements of the mid-19th-century British political elite – most notably Lord Shaftesbury.[ii] The British Foreign Office actively encouraged Jewish emigration to Palestine, exemplified by Charles Henry Churchill‘s 1841–1842 exhortations to Moses Montefiore, the leader of the British Jewish community.[8][a]

Such efforts were premature,[8] and did not succeed;[iii] only 24,000 Jews were living in Palestine on the eve of the emergence of Zionism within the world’s Jewish communities in the last two decades of the 19th century.[10] With the geopolitical shakeup occasioned by the outbreak of the First World War, the earlier calculations, which had lapsed for some time, led to a renewal of strategic assessments and political bargaining over the Middle and Far East.[5]

British anti-Semitism

Although other factors played their part, Jonathan Schneer says that stereotypical thinking by British officials about Jews also played a role in the decision to issue the Declaration. Robert Cecil, Hugh O’Bierne and Sir Mark Sykes all held an unrealistic view of “world Jewry”, the former writing “I do not think it is possible to exaggerate the international power of the Jews.” Zionist representatives saw advantage in encouraging such views.[11][12] James Renton concurs, writing that the British foreign policy elite, including Prime Minister David Lloyd George and Foreign Secretary A.J. Balfour, believed that Jews possessed real and significant power that could be of use to them in the war.[13]

Early Zionism

Further information: ZionismZionism arose in the late 19th century in reaction to anti-Semitic and exclusionary nationalist movements in Europe.[14][iv][v] Romantic nationalism in Central and Eastern Europe had helped to set off the Haskalah, or “Jewish Enlightenment”, creating a split in the Jewish community between those who saw Judaism as their religion and those who saw it as their ethnicity or nation.[14][15] The 1881–1884 anti-Jewish pogroms in the Russian Empire encouraged the growth of the latter identity, resulting in the formation of the Hovevei Zion pioneer organizations, the publication of Leon Pinsker‘s Autoemancipation, and the first major wave of Jewish immigration to Palestine – retrospectively named the “First Aliyah“.[17][18][15]

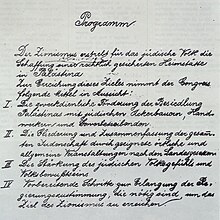

The “Basel program” approved at the 1897 First Zionist Congress. The first line states: “Zionism seeks to establish a home (Heimstätte) for the Jewish people in Palestine secured under public law” In 1896, Theodor Herzl, a Jewish journalist living in Austria-Hungary, published the foundational text of political Zionism, Der Judenstaat (“The Jews’ State” or “The State of the Jews”), in which he asserted that the only solution to the “Jewish Question” in Europe, including growing anti-Semitism, was the establishment of a state for the Jews.[19][20] A year later, Herzl founded the Zionist Organization, which at its first congress called for the establishment of “a home for the Jewish people in Palestine secured under public law”. Proposed measures to attain that goal included the promotion of Jewish settlement there, the organisation of Jews in the diaspora, the strengthening of Jewish feeling and consciousness, and preparatory steps to attain necessary governmental grants.[20] Herzl died in 1904, 44 years before the establishment of State of Israel, the Jewish state that he proposed, without having gained the political standing required to carry out his agenda.[10]

Zionist leader Chaim Weizmann, later President of the World Zionist Organisation and first President of Israel, moved from Switzerland to the UK in 1904 and met Arthur Balfour – who had just launched his 1905–1906 election campaign after resigning as Prime Minister[21] – in a session arranged by Charles Dreyfus, his Jewish constituency representative.[vi] Earlier that year, Balfour had successfully driven the Aliens Act through Parliament with impassioned speeches regarding the need to restrict the wave of immigration into Britain from Jews fleeing the Russian Empire.[23][24] During this meeting, he asked what Weizmann’s objections had been to the 1903 Uganda Scheme that Herzl had supported to provide a portion of British East Africa to the Jewish people as a homeland. The scheme, which had been proposed to Herzl by Joseph Chamberlain, Colonial Secretary in Balfour’s Cabinet, following his trip to East Africa earlier in the year,[vii] had been subsequently voted down following Herzl’s death by the Seventh Zionist Congress in 1905[viii] after two years of heated debate in the Zionist Organization.[27] Weizmann responded that he believed the English are to London as the Jews are to Jerusalem.[b]

In January 1914 Weizmann first met Baron Edmond de Rothschild, a member of the French branch of the Rothschild family and a leading proponent of the Zionist movement,[29] in relation to a project to build a Hebrew university in Jerusalem.[29] The Baron was not part of the World Zionist Organization, but had funded the Jewish agricultural colonies of the First Aliyah and transferred them to the Jewish Colonization Association in 1899.[30] This connection was to bear fruit later that year when the Baron’s son, James de Rothschild, requested a meeting with Weizmann on 25 November 1914, to enlist him in influencing those deemed to be receptive within the British government to their agenda of a “Jewish State” in Palestine.[c][32] Through James’s wife Dorothy, Weizmann was to meet Rózsika Rothschild, who introduced him to the English branch of the family – in particular her husband Charles and his older brother Walter, a zoologist and former Member of Parliament (MP).[33] Their father, Nathan Rothschild, 1st Baron Rothschild, head of the English branch of the family, had a guarded attitude towards Zionism, but he died in March 1915 and his title was inherited by Walter.[33][34]

Prior to the declaration, about 8,000 of Britain’s 300,000 Jews belonged to a Zionist organisation.[35][36] Globally, as of 1913 – the latest known date prior to the declaration – the equivalent figure was approximately 1%.[37]

Ottoman Palestine

Further information: Ottoman Syria and History of Palestine § Restoration of Ottoman controlPublished in 1732, this map by Ottoman geographer Kâtip Çelebi (1609–57) shows the term ارض فلسطين (ʾarḍ Filasṭīn, “Land of Palestine”) extending vertically down the length of the Jordan River.[38]The year 1916 marked four centuries since Palestine had become part of the Ottoman Empire, also known as the Turkish Empire.[39] For most of this period, the Jewish population represented a small minority, approximately 3% of the total, with Muslims representing the largest segment of the population, and Christians the second.[40][41][42][ix]

Ottoman government in Constantinople began to apply restrictions on Jewish immigration to Palestine in late 1882, in response to the start of the First Aliyah earlier that year.[44] Although this immigration was creating a certain amount of tension with the local population, mainly among the merchant and notable classes, in 1901 the Sublime Porte (the Ottoman central government) gave Jews the same rights as Arabs to buy land in Palestine and the percentage of Jews in the population rose to 7% by 1914.[45] At the same time, with growing distrust of the Young Turks (Turkish nationalists who had taken control of the Empire in 1908) and the Second Aliyah, Arab nationalism and Palestinian nationalism was on the rise; and in Palestine anti-Zionism was a characteristic that unified these forces.[45][46] Historians do not know whether these strengthening forces would still have ultimately resulted in conflict in the absence of the Balfour Declaration.[x]

First World War

Further information: Timeline of World War I1914–16: Initial Zionist–British Government discussions

In July 1914 war broke out in Europe between the Triple Entente (Britain, France, and the Russian Empire) and the Central Powers (Germany, Austria-Hungary, and, later that year, the Ottoman Empire).[48]

The British Cabinet first discussed Palestine at a meeting on 9 November 1914, four days after Britain’s declaration of war on the Ottoman Empire, of which the Mutasarrifate of Jerusalem – often referred to as Palestine[49] – was a component. At the meeting David Lloyd George, then Chancellor of the Exchequer, “referred to the ultimate destiny of Palestine”.[50] The Chancellor, whose law firm Lloyd George, Roberts and Co had been engaged a decade before by the Zionist Federation of Great Britain and Ireland to work on the Uganda Scheme,[51] was to become Prime Minister by the time of the declaration, and was ultimately responsible for it.[52]

Herbert Samuel’s Cabinet memorandum, The Future of Palestine, as published in the British Cabinet papers (CAB 37/123/43), as at 21 January 1915 Weizmann’s political efforts picked up speed,[d] and on 10 December 1914 he met with Herbert Samuel, a British Cabinet member and a secular Jew who had studied Zionism;[54] Samuel believed Weizmann’s demands were too modest.[e] Two days later, Weizmann met Balfour again, for the first time since their initial meeting in 1905; Balfour had been out of government ever since his electoral defeat in 1906, but remained a senior member of the Conservative Party in their role as Official Opposition.[f]

A month later, Samuel circulated a memorandum entitled The Future of Palestine to his Cabinet colleagues. The memorandum stated: “I am assured that the solution of the problem of Palestine which would be much the most welcome to the leaders and supporters of the Zionist movement throughout the world would be the annexation of the country to the British Empire”.[57] Samuel discussed a copy of his memorandum with Nathan Rothschild in February 1915, a month before the latter’s death.[34] It was the first time in an official record that enlisting the support of Jews as a war measure had been proposed.[58]

Many further discussions followed, including the initial meetings in 1915–16 between Lloyd George, who had been appointed Minister of Munitions in May 1915,[59] and Weizmann, who was appointed as a scientific advisor to the ministry in September 1915.[60][59] Seventeen years later, in his War Memoirs, Lloyd George described these meetings as being the “fount and origin” of the declaration; historians have rejected this claim.[g]

1915–16: Prior British commitments over Palestine

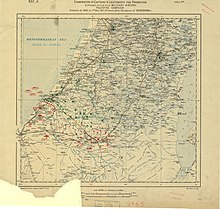

Main articles: McMahon–Hussein Correspondence and Sykes–Picot AgreementExcerpts from CAB 24/68/86 (Nov. 1918) and the Churchill White Paper (June 1922)Map from FO 371/4368 (Nov. 1918) showing Palestine in the “Arab” area[67]In late 1915 the British High Commissioner to Egypt, Henry McMahon, exchanged ten letters with Hussein bin Ali, Sharif of Mecca, in which he promised Hussein to recognize Arab independence “in the limits and boundaries proposed by the Sherif of Mecca” in return for Hussein launching a revolt against the Ottoman Empire. The pledge excluded “portions of Syria” lying to the west of “the districts of Damascus, Homs, Hama and Aleppo“.[68][h] In the decades after the war, the extent of this coastal exclusion was hotly disputed[70] since Palestine lay to the southwest of Damascus and was not explicitly mentioned.[68]

The Arab Revolt was launched on June 5th, 1916,[73] on the basis of the quid pro quo agreement in the correspondence.[74] However, less than three weeks earlier the governments of the United Kingdom, France, and Russia secretly concluded the Sykes–Picot Agreement, which Balfour described later as a “wholly new method” for dividing the region, after the 1915 agreement “seems to have been forgotten”.[j]

This Anglo-French treaty was negotiated in late 1915 and early 1916 between Sir Mark Sykes and François Georges-Picot, with the primary arrangements being set out in draft form in a joint memorandum on 5 January 1916.[76][77] Sykes was a British Conservative MP who had risen to a position of significant influence on Britain’s Middle East policy, beginning with his seat on the 1915 De Bunsen Committee and his initiative to create the Arab Bureau.[78] Picot was a French diplomat and former consul-general in Beirut.[78] Their agreement defined the proposed spheres of influence and control in Western Asia should the Triple Entente succeed in defeating the Ottoman Empire during World War I,[79][80] dividing many Arab territories into British- and French-administered areas. In Palestine, internationalisation was proposed,[79][80] with the form of administration to be confirmed after consultation with both Russia and Hussein;[79] the January draft noted Christian and Muslim interests, and that “members of the Jewish community throughout the world have a conscientious and sentimental interest in the future of the country.”[77][81][k]

Prior to this point, no active negotiations with Zionists had taken place, but Sykes had been aware of Zionism, was in contact with Moses Gaster – a former President of the English Zionist Federation[83] – and may have seen Samuel’s 1915 memorandum.[81][84] On 3 March, while Sykes and Picot were still in Petrograd, Lucien Wolf (secretary of the Foreign Conjoint Committee, set up by Jewish organizations to further the interests of foreign Jews) submitted to the Foreign Office, the draft of an assurance (formula) that could be issued by the allies in support of Jewish aspirations:

In the event of Palestine coming within the spheres of influence of Great Britain or France at the close of the war, the governments of those powers will not fail to take account of the historic interest that country possesses for the Jewish community. The Jewish population will be secured in the enjoyment of civil and religious liberty, equal political rights with the rest of the population, reasonable facilities for immigration and colonisation, and such municipal privileges in the towns and colonies inhabited by them as may be shown to be necessary.

On 11 March, telegrams[l] were sent in Grey’s name to Britain’s Russian and French ambassadors for transmission to Russian and French authorities, including the formula, as well as:

The scheme might be made far more attractive to the majority of Jews if it held out to them the prospect that when in course of time the Jewish colonists in Palestine grow strong enough to cope with the Arab population they may be allowed to take the management of the internal affairs of Palestine (with the exception of Jerusalem and the holy places) into their own hands.

Sykes, having seen the telegram, had discussions with Picot and proposed (making reference to Samuel’s memorandum[m]) the creation of an Arab Sultanate under French and British protection, some means of administering the holy places along with the establishment of a company to purchase land for Jewish colonists, who would then become citizens with equal rights to Arabs.[n]

Shortly after returning from Petrograd, Sykes briefed Samuel, who then briefed a meeting of Gaster, Weizmann and Sokolow. Gaster recorded in his diary on 16 April 1916: “We are offered French-English condominium in Palest[ine]. Arab Prince to conciliate Arab sentiment and as part of the Constitution a Charter to Zionists for which England would stand guarantee and which would stand by us in every case of friction … It practically comes to a complete realisation of our Zionist programme. However, we insisted on: national character of Charter, freedom of immigration and internal autonomy, and at the same time full rights of citizenship to [illegible] and Jews in Palestine.”[86] In Sykes’ mind, the agreement which bore his name was outdated even before it was signed – in March 1916, he wrote in a private letter: “to my mind the Zionists are now the key of the situation”.[xii][88] In the event, neither the French nor the Russians were enthusiastic about the proposed formulation and eventually on 4 July, Wolf was informed that “the present moment is inopportune for making any announcement.”[89]

These wartime initiatives, inclusive of the declaration, are frequently considered together by historians because of the potential, real or imagined, for incompatibility between them, particularly in regard to the disposition of Palestine.[90] In the words of Professor Albert Hourani, founder of the Middle East Centre at St Antony’s College, Oxford: “The argument about the interpretation of these agreements is one which is impossible to end, because they were intended to bear more than one interpretation.”[91]

1916–17: Change in British Government

In terms of British politics, the declaration resulted from the coming into power of Lloyd George and his Cabinet, which had replaced the H. H. Asquith led-Cabinet in December 1916. Whilst both Prime Ministers were Liberals and both governments were wartime coalitions, Lloyd George and Balfour, appointed as his Foreign Secretary, favoured a post-war partition of the Ottoman Empire as a major British war aim, whereas Asquith and his Foreign Secretary, Sir Edward Grey, had favoured its reform.[92][93]

Two days after taking office, Lloyd George told General Robertson, the Chief of the Imperial General Staff, that he wanted a major victory, preferably the capture of Jerusalem, to impress British public opinion,[94] and immediately consulted his War Cabinet about a “further campaign into Palestine when El Arish had been secured.”[95] Subsequent pressure from Lloyd George, over the reservations of Robertson, resulted in the recapture of the Sinai for British-controlled Egypt, and, with the capture of El Arish in December 1916 and Rafah in January 1917, the arrival of British forces at the southern borders of the Ottoman Empire.[95] Following two unsuccessful attempts to capture Gaza between 26 March and 19 April, a six-month stalemate in Southern Palestine began;[96] the Sinai and Palestine Campaign would not make any progress into Palestine until 31 October 1917.[97]

1917: British-Zionist formal negotiations

Following the change in government, Sykes was promoted into the War Cabinet Secretariat with responsibility for Middle Eastern affairs. In January 1917, despite having previously built a relationship with Moses Gaster,[xiii] he began looking to meet other Zionist leaders; by the end of the month he had been introduced to Weizmann and his associate Nahum Sokolow, a journalist and executive of the World Zionist Organization who had moved to Britain at the beginning of the war.[xiv]

On 7 February 1917, Sykes, claiming to be acting in a private capacity, entered into substantive discussions with the Zionist leadership.[o] The previous British correspondence with “the Arabs” was discussed at the meeting; Sokolow’s notes record Sykes’ description that “The Arabs professed that language must be the measure [by which control of Palestine should be determined] and [by that measure] could claim all Syria and Palestine. Still the Arabs could be managed, particularly if they received Jewish support in other matters.”[100][101][p] At this point the Zionists were still unaware of the Sykes-Picot Agreement, although they had their suspicions.[100] One of Sykes’ goals was the mobilization of Zionism to the cause of British suzerainty in Palestine, so as to have arguments to put to France in support of that objective.[103]

Late 1917: Progress of the wider war

Military situation at 18:00 on 1 Nov 1917, immediately prior to the release of the Balfour Declaration. During the period of the British War Cabinet discussions leading up to the declaration, the war had reached a period of stalemate. On the Western Front the tide would first turn in favour of the Central Powers in spring 1918,[104] before decisively turning in favour of the Allies from July 1918 onwards.[104] Although the United States declared war on Germany in the spring of 1917, it did not suffer its first casualties until 2 November 1917,[105] at which point President Woodrow Wilson still hoped to avoid dispatching large contingents of troops into the war.[106] The Russian forces were known to be distracted by the ongoing Russian Revolution and the growing support for the Bolshevik faction, but Alexander Kerensky‘s Provisional Government had remained in the war; Russia only withdrew after the final stage of the revolution on 7 November 1917.[107]

Approvals

April to June: Allied discussions

Balfour met Weizmann at the Foreign Office on 22 March 1917; two days later, Weizmann described the meeting as being “the first time I had a real business talk with him”.[108] Weizmann explained at the meeting that the Zionists had a preference for a British protectorate over Palestine, as opposed to an American, French or international arrangement; Balfour agreed, but warned that “there may be difficulties with France and Italy”.[108]

The French position in regard to Palestine and the wider Syria region during the lead up to the Balfour Declaration was largely dictated by the terms of the Sykes-Picot Agreement and was complicated from 23 November 1915 by increasing French awareness of the British discussions with the Sherif of Mecca.[109] Prior to 1917, the British had led the fighting on the southern border of the Ottoman Empire alone, given their neighbouring Egyptian colony and the French preoccupation with the fighting on the Western Front that was taking place on their own soil.[110][111] Italy’s participation in the war, which began following the April 1915 Treaty of London, did not include involvement in the Middle Eastern sphere until the April 1917 Agreement of Saint-Jean-de-Maurienne; at this conference, Lloyd George had raised the question of a British protectorate of Palestine and the idea “had been very coldly received” by the French and the Italians.[112][113][q] In May and June 1917, the French and Italians sent detachments to support the British as they built their reinforcements in preparation for a renewed attack on Palestine.[110][111]

In early April, Sykes and Picot were appointed to act as the chief negotiators once more, this time on a month-long mission to the Middle East for further discussions with the Sherif of Mecca and other Arab leaders.[114][r] On 3 April 1917, Sykes met with Lloyd George, Lord Curzon and Maurice Hankey to receive his instructions in this regard, namely to keep the French onside while “not prejudicing the Zionist movement and the possibility of its development under British auspices, [and not] enter into any political pledges to the Arabs, and particularly none in regard to Palestine”.[116] Before travelling to the Middle East, Picot, via Sykes, invited Nahum Sokolow to Paris to educate the French government on Zionism.[117] Sykes, who had prepared the way in correspondence with Picot,[118] arrived a few days after Sokolow; in the meantime, Sokolow had met Picot and other French officials, and convinced the French Foreign Office to accept for study a statement of Zionist aims “in regard to facilities of colonization, communal autonomy, rights of language and establishment of a Jewish chartered company.”[119] Sykes went on ahead to Italy and had meetings with the British ambassador and British Vatican representative to prepare the way for Sokolow once again.[120]

Sokolow was granted an audience with Pope Benedict XV on 6 May 1917.[121] Sokolow’s notes of the meeting – the only meeting records known to historians – stated that the Pope expressed general sympathy and support for the Zionist project.[122][xv] On 21 May 1917 Angelo Sereni, president of the Committee of the Jewish Communities,[s] presented Sokolow to Sidney Sonnino, the Italian Minister of Foreign Affairs. He was also received by Paolo Boselli, the Italian prime minister. Sonnino arranged for the secretary general of the ministry to send a letter to the effect that, although he could not express himself on the merits of a program which concerned all the allies, “generally speaking” he was not opposed to the legitimate claims of the Jews.[128] On his return journey, Sokolow met with French leaders again and secured a letter dated 4 June 1917, giving assurances of sympathy towards the Zionist cause by Jules Cambon, head of the political section of the French foreign ministry.[129] This letter was not published, but was deposited at the British Foreign Office.[130][xvi]

Following the United States’ entry into the war on 6 April, the British Foreign Secretary led the Balfour Mission to Washington, D.C., and New York, where he spent a month between mid-April and mid-May. During the trip he spent significant time discussing Zionism with Louis Brandeis, a leading Zionist and a close ally of Wilson who had been appointed as a Supreme Court Justice a year previously.[t]

June and July: Decision to prepare a declaration

A copy of Lord Rothschild’s initial draft declaration, together with its covering letter, 18 July 1917, from the British War Cabinet archives. By 13 June 1917, it was acknowledged by Ronald Graham, head of the Foreign Office’s Middle Eastern affairs department, that the three most relevant politicians – the Prime Minister, the Foreign Secretary, and the Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, Lord Robert Cecil – were all in favour of Britain supporting the Zionist movement;[u] on the same day Weizmann had written to Graham to advocate for a public declaration.[v][134][135]

Six days later, at a meeting on 19 June, Balfour asked Lord Rothschild and Weizmann to submit a formula for a declaration.[136] Over the next few weeks, a 143-word draft was prepared by the Zionist negotiating committee, but it was considered too specific on sensitive areas by Sykes, Graham and Rothschild.[137] Separately, a very different draft had been prepared by the Foreign Office, described in 1961 by Harold Nicolson – who had been involved in preparing the draft – as proposing a “sanctuary for Jewish victims of persecution”.[138][139] The Foreign Office draft was strongly opposed by the Zionists, and was discarded; no copy of the draft has been found in the Foreign Office archives.[138][139]

Following further discussion, a revised – and at just 46 words in length, much shorter – draft declaration was prepared and sent by Lord Rothschild to Balfour on 18 July.[137] It was received by the Foreign Office, and the matter was brought to the Cabinet for formal consideration.[140]

September and October: American consent and War Cabinet approval

As part of the War Cabinet discussions, views were sought from ten “representative” Jewish leaders. Those in favour comprised four members of the Zionist negotiating team (Rothschild, Weizmann, Sokolow and Samuel), Stuart Samuel (Herbert Samuel’s elder brother), and Chief Rabbi Joseph Hertz. Those against comprised Edwin Montagu, Philip Magnus, Claude Montefiore and Lionel Cohen. The decision to release the declaration was taken by the British War Cabinet on 31 October 1917. This followed discussion at four War Cabinet meetings (including the 31 October meeting) over the space of the previous two months.[140] In order to aid the discussions, the War Cabinet Secretariat, led by Maurice Hankey, the Cabinet Secretary and supported by his Assistant Secretaries[141][142] – primarily Sykes and his fellow Conservative MP and pro-Zionist Leo Amery – solicited outside perspectives to put before the Cabinet. These included the views of government ministers, war allies – notably from President Woodrow Wilson – and in October, formal submissions from six Zionist leaders and four non-Zionist Jews.[140]

British officials asked President Wilson for his consent on the matter on two occasions – first on 3 September, when he replied the time was not ripe, and later on 6 October, when he agreed with the release of the declaration.[143]

British War Cabinet minutes approving the release of the declaration, 31 October 1917 Excerpts from the minutes of these four War Cabinet meetings provide a description of the primary factors that the ministers considered:

- 3 September 1917: “With reference to a suggestion that the matter might be postponed, [Balfour] pointed out that this was a question on which the Foreign Office had been very strongly pressed for a long time past. There was a very strong and enthusiastic organisation, more particularly in the United States, who were zealous in this matter, and his belief was that it would be of most substantial assistance to the Allies to have the earnestness and enthusiasm of these people enlisted on our side. To do nothing was to risk a direct breach with them, and it was necessary to face this situation.”[144]

- 4 October 1917: “… [Balfour] stated that the German Government were making great efforts to capture the sympathy of the Zionist Movement. This Movement, though opposed by a number of wealthy Jews in this country, had behind it the support of a majority of Jews, at all events in Russia and America, and possibly in other countries … Mr. Balfour then read a very sympathetic declaration by the French Government which had been conveyed to the Zionists, and he stated that he knew that President Wilson was extremely favourable to the Movement.”[145]

- 25 October 1917: “… the Secretary mentioned that he was being pressed by the Foreign Office to bring forward the question of Zionism, an early settlement of which was regarded as of great importance.”[146]

- 31 October 1917: “[Balfour] stated that he gathered that everyone was now agreed that, from a purely diplomatic and political point of view, it was desirable that some declaration favourable to the aspirations of the Jewish nationalists should now be made. The vast majority of Jews in Russia and America, as, indeed, all over the world, now appeared to be favourable to Zionism. If we could make a declaration favourable to such an ideal, we should be able to carry on extremely useful propaganda both in Russia and America.”[147]

Drafting

Declassification of British government archives has allowed scholars to piece together the choreography of the drafting of the declaration; in his widely cited 1961 book, Leonard Stein published four previous drafts of the declaration.[148]

The drafting began with Weizmann’s guidance to the Zionist drafting team on its objectives in a letter dated 20 June 1917, one day following his meeting with Rothschild and Balfour. He proposed that the declaration from the British government should state: “its conviction, its desire or its intention to support Zionist aims for the creation of a Jewish national home in Palestine; no reference must be made I think to the question of the Suzerain Power because that would land the British into difficulties with the French; it must be a Zionist declaration.”[92][149]

A month after the receipt of the much-reduced 12 July draft from Rothschild, Balfour proposed a number of mainly technical amendments.[148] The two subsequent drafts included much more substantial amendments: the first in a late August draft by Lord Milner – one of the original five members of Lloyd George’s War Cabinet as a minister without portfolio[xvii] – which reduced the geographic scope from all of Palestine to “in Palestine”, and the second from Milner and Amery in early October, which added the two “safeguard clauses”.[148]

List of known drafts of the Balfour Declaration, showing changes between each draft Subsequent authors have debated who the “primary author” really was. In his posthumously published 1981 book The Anglo-American Establishment, Georgetown University history professor Carroll Quigley explained his view that Lord Milner was the primary author of the declaration,[xviii] and more recently, William D. Rubinstein, Professor of Modern History at Aberystwyth University, Wales, proposed Amery instead.[153] Huneidi wrote that Ormsby-Gore, in a report he prepared for Shuckburgh, claimed authorship, together with Amery, of the final draft form.[154]

Key issues

The agreed version of the declaration, a single sentence of just 67 words,[155] was sent on 2 November 1917 in a short letter from Balfour to Walter Rothschild, for transmission to the Zionist Federation of Great Britain and Ireland.[156] The declaration contained four clauses, of which the first two promised to support “the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people”, followed by two “safeguard clauses”[157][158] with respect to “the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine”, and “the rights and political status enjoyed by Jews in any other country”.[156]

The “national home for the Jewish people” vs. Jewish state

Further information: Homeland for the Jewish people“This is a very carefully worded document and but for the somewhat vague phrase ‘A National Home for the Jewish People’ might be considered sufficiently unalarming … But the vagueness of the phrase cited has been a cause of trouble from the commencement. Various persons in high positions have used language of the loosest kind calculated to convey a very different impression to the more moderate interpretation which can be put upon the words. President Wilson brushed away all doubts as to what was intended from his point of view when, in March 1919, he said to the Jewish leaders in America, ‘I am moreover persuaded that the allied nations, with the fullest concurrence of our own Government and people are agreed that in Palestine shall be laid the foundations of a Jewish Commonwealth.’[w] The late President Roosevelt declared that one of the Allies peace conditions should be that ‘Palestine must be made a Jewish State.’ Mr. Winston Churchill has spoken of a ‘Jewish State’ and Mr. Bonar Law has talked in Parliament of ‘restoring Palestine to the Jews’.”[160][x]

Report of the Palin Commission, August 1920[162]

The term “national home” was intentionally ambiguous,[163] having no legal value or precedent in international law,[156] such that its meaning was unclear when compared to other terms such as “state”.[156] The term was intentionally used instead of “state” because of opposition to the Zionist program within the British Cabinet.[156] According to historian Norman Rose, the chief architects of the declaration contemplated that a Jewish State would emerge in time while the Palestine Royal Commission concluded that the wording was “the outcome of a compromise between those Ministers who contemplated the ultimate establishment of a Jewish State and those who did not.”[164][xix]

Interpretation of the wording has been sought in the correspondence leading to the final version of the declaration. An official report to the War Cabinet sent by Sykes on 22 September said that the Zionists did not want “to set up a Jewish Republic or any other form of state in Palestine or in any part of Palestine” but rather preferred some form of protectorate as provided in the Palestine Mandate.[y] A month later, Curzon produced a memorandum[167] circulated on 26 October 1917 where he addressed two questions, the first concerning the meaning of the phrase “a National Home for the Jewish race in Palestine”; he noted that there were different opinions ranging from a fully fledged state to a merely spiritual centre for the Jews.[168]

Sections of the British press assumed that a Jewish state was intended even before the Declaration was finalized.[xx] In the United States the press began using the terms “Jewish National Home”, “Jewish State”, “Jewish republic” and “Jewish Commonwealth” interchangeably.[170]

Treaty expert David Hunter Miller, who was at the conference and subsequently compiled a 22 volume compendium of documents, provides a report of the Intelligence Section of the American Delegation to the Paris Peace Conference of 1919 which recommended that “there be established a separate state in Palestine,” and that “it will be the policy of the League of Nations to recognize Palestine as a Jewish state, as soon as it is a Jewish state in fact.”[171][172] The report further advised that an independent Palestinian state under a British League of Nations mandate be created. Jewish settlement would be allowed and encouraged in this state and this state’s holy sites would be under the control of the League of Nations.[172] Indeed, the Inquiry spoke positively about the possibility of a Jewish state eventually being created in Palestine if the necessary demographics for this were to exist.[172]

Historian Matthew Jacobs later wrote that the US approach was hampered by the “general absence of specialist knowledge about the region” and that “like much of the Inquiry’s work on the Middle East, the reports on Palestine were deeply flawed” and “presupposed a particular outcome of the conflict”. He quotes Miller, writing about one report on the history and impact of Zionism, “absolutely inadequate from any standpoint and must be regarded as nothing more than material for a future report”.[173]

Lord Robert Cecil on 2 December 1917, assured an audience that the government fully intended that “Judea [was] for the Jews.”[171] Yair Auron opines that Cecil, then a deputy Foreign Secretary representing the British Government at a celebratory gathering of the English Zionist Federation, “possibly went beyond his official brief” in saying (he cites Stein) “Our wish is that Arabian countries shall be for the Arabs, Armenia for the Armenians and Judaea for the Jews”.[174]

The following October Neville Chamberlain, while chairing a Zionist meeting, discussed a “new Jewish State.”[171] At the time, Chamberlain was a Member of Parliament for Ladywood, Birmingham; recalling the event in 1939, just after Chamberlain had approved the 1939 White Paper, the Jewish Telegraph Agency noted that the Prime Minister had “experienced a pronounced change of mind in the 21 years intervening”[175] A year later, on the Declaration’s second anniversary, General Jan Smuts said that Britain “would redeem her pledge … and a great Jewish state would ultimately rise.”[171] In similar vein, Churchill a few months later stated:

If, as may well happen, there should be created in our own lifetime by the banks of the Jordan a Jewish State under the protection of the British Crown which might comprise three or four millions of Jews, an event will have occurred in the history of the world which would from every point of view be beneficial.[176]

At the 22 June 1921 meeting of the Imperial Cabinet, Churchill was asked by Arthur Meighen, the Canadian Prime Minister, about the meaning of the national home. Churchill said “If in the course of many years they become a majority in the country, they naturally would take it over … pro rata with the Arab. We made an equal pledge that we would not turn the Arab off his land or invade his political and social rights”.[177]

Lord Curzon’s 26 October 1917 cabinet memorandum, circulated one week prior to the declaration, addressed the meaning of the phrase “a National Home for the Jewish race in Palestine”, noting the range of different opinions[167] Responding to Curzon in January 1919, Balfour wrote “Weizmann has never put forward a claim for the Jewish Government of Palestine. Such a claim in my opinion is clearly inadmissible and personally I do not think we should go further than the original declaration which I made to Lord Rothschild”.[178]

In February 1919, France issued a statement that it would not oppose putting Palestine under British trusteeship and the formation of a Jewish State.[171] Friedman further notes that France’s attitude went on to change;[171] Yehuda Blum, while discussing France’s “unfriendly attitude towards the Jewish national movement”, notes the content of a report made by Robert Vansittart (a leading member of the British delegation to the Paris Peace Conference) to Curzon in November 1920 which said:

[The French] had agreed to a Jewish National Home (capitalized in the source), not a Jewish State. They considered we were steering straight upon the latter, and the very last thing they would do was to enlarge that State for they totally disapproved our policy.[179]

Greece’s Foreign Minister told the editor of the Salonica Jewish organ Pro-Israel that “the establishment of a Jewish State meets in Greece with full and sincere sympathy … A Jewish Palestine would become an ally of Greece.”[171] In Switzerland, a number of noted historians including professors Tobler, Forel-Yvorne, and Rogaz, supported the idea of establishing a Jewish state, with one referring to it as “a sacred right of the Jews.”[171] While in Germany, officials and most of the press took the Declaration to mean a British sponsored state for the Jews.[171]

The British government, including Churchill, made it clear that the Declaration did not intend for the whole of Palestine to be converted into a Jewish National Home, “but that such a Home should be founded in Palestine.”[xxii][xxiii] Emir Faisal, King of Syria and Iraq, made a formal written agreement with Zionist leader Chaim Weizmann, which was drafted by T.E. Lawrence, whereby they would try to establish a peaceful relationship between Arabs and Jews in Palestine.[186] The 3 January 1919 Faisal–Weizmann Agreement was a short-lived agreement for Arab–Jewish cooperation on the development of a Jewish homeland in Palestine.[z] Faisal did treat Palestine differently in his presentation to the Peace Conference on 6 February 1919 saying “Palestine, for its universal character, [should be] left on one side for the mutual consideration of all parties concerned”.[188][189] The agreement was never implemented.[aa] In a subsequent letter written in English by Lawrence for Faisal’s signature, he explained:

We feel that the Arabs and Jews are cousins in race, suffering similar oppression at the hands of powers stronger than themselves, and by a happy coincidence have been able to take the first step toward the attainment of their national ideals together. We Arabs, especially the educated among us, look with deepest sympathy on the Zionist movement … We will do our best, in so far as we are concerned, to help them through; we will wish the Jews a most hearty welcome home.[186]

When the letter was tabled at the Shaw Commission in 1929, Rustam Haidar spoke to Faisal in Baghdad and cabled that Faisal had “no recollection that he wrote anything of the sort”.[192] In January 1930, Haidar wrote to a newspaper in Baghdad that Faisal: “finds it exceedingly strange that such a matter is attributed to him as he at no time would consider allowing any foreign nation to share in an Arab country”.[192] Awni Abd al-Hadi, Faisal’s secretary, wrote in his memoirs that he was not aware that a meeting between Frankfurter and Faisal took place and that: “I believe that this letter, assuming that it is authentic, was written by Lawrence, and that Lawrence signed it in English on behalf of Faisal. I believe this letter is part of the false claims made by Chaim Weizmann and Lawrence to lead astray public opinion.”[192] According to Allawi, the most likely explanation for the Frankfurter letter is that a meeting took place, a letter was drafted in English by Lawrence, but that its “contents were not entirely made clear to Faisal. He then may or may not have been induced to sign it”, since it ran counter to Faisal’s other public and private statements at the time.[193] A 1 March interview by Le Matin quoted Faisal as saying:

This feeling of respect for other religions dictates my opinion about Palestine, our neighbor. That the unhappy Jews come to reside there and behave as good citizens of this country, our humanity rejoices given that they are placed under a Muslim or Christian government mandated by The League of Nations. If they want to constitute a state and claim sovereign rights in this region, I foresee very serious dangers. It is to be feared that there will be a conflict between them and the other races.[194][ab]

Referring to his 1922 White Paper, Churchill later wrote that “there is nothing in it to prohibit the ultimate establishment of a Jewish State.”[195] And in private, many British officials agreed with the Zionists’ interpretation that a state would be established when a Jewish majority was achieved.[196]

When Chaim Weizmann met with Churchill, Lloyd George and Balfour at Balfour’s home in London on 21 July 1921, Lloyd George and Balfour assured Weizmann “that by the Declaration they had always meant an eventual Jewish State,” according to Weizmann minutes of that meeting.[197] Lloyd George stated in 1937 that it was intended that Palestine would become a Jewish Commonwealth if and when Jews “had become a definite majority of the inhabitants”,[ac] and Leo Amery echoed the same position in 1946.[ad] In the UNSCOP report of 1947, the issue of home versus state was subjected to scrutiny arriving at a similar conclusion to that of Lloyd George.[xxiv]

Scope of the national home “in Palestine”

The statement that such a homeland would be found “in Palestine” rather than “of Palestine” was also deliberate.[xxv] The proposed draft of the declaration contained in Rothschild’s 12 July letter to Balfour referred to the principle “that Palestine should be reconstituted as the National Home of the Jewish people.”[202] In the final text, following Lord Milner’s amendment, the word “reconstituted” was removed and the word “that” was replaced with “in”.[203][204]

This text thereby avoided committing the entirety of Palestine as the National Home of the Jewish people, resulting in controversy in future years over the intended scope, especially the Revisionist Zionism sector, which claimed entirety of Mandatory Palestine and Emirate of Transjordan as Jewish Homeland[150][203] This was clarified by the 1922 Churchill White Paper, which wrote that “the terms of the declaration referred to do not contemplate that Palestine as a whole should be converted into a Jewish National Home, but that such a Home should be founded ‘in Palestine.'”[205]

The declaration did not include any geographical boundaries for Palestine.[206] Following the end of the war, three documents – the declaration, the Hussein-McMahon Correspondence and the Sykes-Picot Agreement – became the basis for the negotiations to set the boundaries of Palestine.[207]

Civil and religious rights of non-Jewish communities in Palestine

“If, however, the strict terms of the Balfour Statement are adhered to … it can hardly be doubted that the extreme Zionist Program must be greatly modified. For “a national home for the Jewish people” is not equivalent to making Palestine into a Jewish State; nor can the erection of such a Jewish State be accomplished without the gravest trespass upon the “civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine.” The fact came out repeatedly in the Commission’s conference with Jewish representatives, that the Zionists looked forward to a practically complete dispossession of the present non-Jewish inhabitants of Palestine, by various forms of purchase.”

Report of the King–Crane Commission, August 1919[208]

The declaration’s first safeguard clause referred to protecting the civil and religious rights of non-Jews in Palestine. The clause had been drafted together with the second safeguard by Leo Amery in consultation with Lord Milner, with the intention to “go a reasonable distance to meeting the objectors, both Jewish and pro-Arab, without impairing the substance of the proposed declaration”.[209][ae]

The “non-Jews” constituted 90% of the population of Palestine;[211] in the words of Ronald Storrs, Britain’s Military Governor of Jerusalem between 1917 and 1920, the community observed that they had been “not so much as named, either as Arabs, Moslems or Christians, but were lumped together under the negative and humiliating definition of ‘Non-Jewish Communities’ and relegated to subordinate provisos”.[af] The community also noted that there was no reference to protecting their “political status” or political rights, as there was in the subsequent safeguard relating to Jews in other countries.[212][213] This protection was frequently contrasted against the commitment to the Jewish community, and over the years a variety of terms were used to refer to these two obligations as a pair;[ag] a particularly heated question was whether these two obligations had “equal weight”, and in 1930 this equal status was confirmed by the Permanent Mandates Commission and by the British government in the Passfield white paper.[ah]

Balfour stated in February 1919 that Palestine was considered an exceptional case in which, referring to the local population, “we deliberately and rightly decline to accept the principle of self-determination,”[ai] although he considered that the policy provided self-determination to Jews.[219] Avi Shlaim considers this the declaration’s “greatest contradiction”.[90] This principle of self-determination had been declared on numerous occasions subsequent to the declaration – President Wilson’s January 1918 Fourteen Points, McMahon’s Declaration to the Seven in June 1918, the November 1918 Anglo-French Declaration, and the June 1919 Covenant of the League of Nations that had established the mandate system.[aj] In an August 1919 memo Balfour acknowledged the inconsistency among these statements, and further explained that the British had no intention of consulting the existing population of Palestine.[ak] The results of the ongoing American King–Crane Commission of Enquiry consultation of the local population – from which the British had withdrawn – were suppressed for three years until the report was leaked in 1922.[225] Subsequent British governments have acknowledged this deficiency, in particular the 1939 committee led by the Lord Chancellor, Frederic Maugham, which concluded that the government had not been “free to dispose of Palestine without regard for the wishes and interests of the inhabitants of Palestine”,[226] and the April 2017 statement by British Foreign Office minister of state Baroness Anelay that the government acknowledged that “the Declaration should have called for the protection of political rights of the non-Jewish communities in Palestine, particularly their right to self-determination.”[al][am]

Rights and political status of Jews in other countries

Edwin Montagu, the only Jew in a senior British government position,[230] wrote a 23 August 1917 memorandum stating his belief that: “the policy of His Majesty’s Government is anti-Semitic in result and will prove a rallying ground for anti-Semites in every country of the world.” The second safeguard clause was a commitment that nothing should be done which might prejudice the rights of the Jewish communities in other countries outside of Palestine.[231] The original drafts of Rothschild, Balfour, and Milner did not include this safeguard, which was drafted together with the preceding safeguard in early October,[231] in order to reflect opposition from influential members of the Anglo-Jewish community.[231] Lord Rothschild took exception to the proviso on the basis that it presupposed the possibility of a danger to non-Zionists, which he denied.[232]

The Conjoint Foreign Committee of the Board of Deputies of British Jews and the Anglo-Jewish Association had published a letter in The Times on 24 May 1917 entitled Views of Anglo-Jewry, signed by the two organisations’ presidents, David Lindo Alexander and Claude Montefiore, stating their view that: “the establishment of a Jewish nationality in Palestine, founded on this theory of homelessness, must have the effect throughout the world of stamping the Jews as strangers in their native lands, and of undermining their hard-won position as citizens and nationals of these lands.”[233] This was followed in late August by Edwin Montagu, an influential anti-Zionist Jew and Secretary of State for India, and the only Jewish member of the British Cabinet, who wrote in a Cabinet memorandum that: “The policy of His Majesty’s Government is anti-Semitic in result and will prove a rallying ground for anti-Semites in every country of the world.”[234]

Reaction

The text of the declaration was published in the press one week after it was signed, on 9 November 1917.[235] Other related events took place within a short timeframe, the two most relevant being the almost immediate British military capture of Palestine and the leaking of the previously secret Sykes-Picot Agreement. On the military side, both Gaza and Jaffa fell within several days, and Jerusalem was surrendered to the British on 9 December.[97] The publication of the Sykes–Picot Agreement, following the Russian Revolution, in the Bolshevik Izvestia and Pravda on 23 November 1917 and in the British Manchester Guardian on 26 November 1917, represented a dramatic moment for the Allies’ Eastern campaign:[236][237] “the British were embarrassed, the Arabs dismayed and the Turks delighted.”[238] The Zionists had been aware of the outlines of the agreement since April and specifically the part relevant to Palestine, following a meeting between Weizmann and Cecil where Weizmann made very clear his objections to the proposed scheme.[239]

Zionist reaction

Balfour Declaration as published in The Times, 9 November 1917 The declaration represented the first public support for Zionism by a major political power[240] – its publication galvanized Zionism, which finally had obtained an official charter.[241] In addition to its publication in major newspapers, leaflets were circulated throughout Jewish communities. These leaflets were airdropped over Jewish communities in Germany and Austria, as well as the Pale of Settlement, which had been given to the Central Powers following the Russian withdrawal.[242]

Weizmann had argued that the declaration would have three effects: it would swing Russia to maintain pressure on Germany’s Eastern Front, since Jews had been prominent in the March Revolution of 1917; it would rally the large Jewish community in the United States to press for greater funding for the American war effort, underway since April of that year; and, lastly, that it would undermine German Jewish support for Kaiser Wilhelm II.[243]

The declaration spurred an unintended and extraordinary increase in the number of adherents of American Zionism; in 1914 the 200 American Zionist societies comprised a total of 7,500 members, which grew to 30,000 members in 600 societies in 1918 and 149,000 members in 1919.[xxvi] Whilst the British had considered that the declaration reflected a previously established dominance of the Zionist position in Jewish thought, it was the declaration itself that was subsequently responsible for Zionism’s legitimacy and leadership.[xxvii]

Exactly one month after the declaration was issued, a large-scale celebration took place at the Royal Opera House – speeches were given by leading Zionists as well as members of the British administration including Sykes and Cecil.[245] From 1918 until the Second World War, Jews in Mandatory Palestine celebrated Balfour Day as an annual national holiday on 2 November.[246] The celebrations included ceremonies in schools and other public institutions and festive articles in the Hebrew press.[246] In August 1919 Balfour approved Weizmann’s request to name the first post-war settlement in Mandatory Palestine, “Balfouria“, in his honour.[247][248] It was intended to be a model settlement for future American Jewish activity in Palestine.[249]

Herbert Samuel, the Zionist MP whose 1915 memorandum had framed the start of discussions in the British Cabinet, was asked by Lloyd George on 24 April 1920 to act as the first civil governor of British Palestine, replacing the previous military administration that had ruled the area since the war.[250] Shortly after beginning the role in July 1920, he was invited to read the haftarah from Isaiah 40 at the Hurva Synagogue in Jerusalem,[251] which, according to his memoirs, led the congregation of older settlers to feel that the “fulfilment of ancient prophecy might at last be at hand”.[an][253]

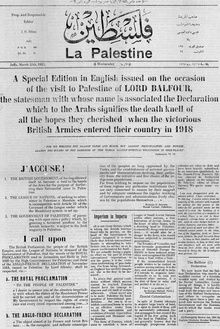

Opposition in Palestine

The most popular Palestinian Arab newspaper, Filastin, published a four-page editorial addressed to Lord Balfour in March 1925. The editorial begins with “J’Accuse!”, in a reference to the outrage at French anti-semitism 27 years previously. The local Christian and Muslim community of Palestine, who constituted almost 90% of the population, strongly opposed the declaration.[211] As described by the Palestinian-American philosopher Edward Said in 1979, it was perceived as being made: “(a) by a European power, (b) about a non-European territory, (c) in a flat disregard of both the presence and the wishes of the native majority resident in that territory, and (d) it took the form of a promise about this same territory to another foreign group.”[xxviii]

According to the 1919 King–Crane Commission, “No British officer, consulted by the Commissioners, believed that the Zionist programme could be carried out except by force of arms.”[255] A delegation of the Muslim-Christian Association, headed by Musa al-Husayni, expressed public disapproval on 3 November 1918, one day after the Zionist Commission parade marking the first anniversary of the Balfour Declaration.[256] They handed a petition signed by more than 100 notables to Ronald Storrs, the British military governor:

We have noticed yesterday a large crowd of Jews carrying banners and over-running the streets shouting words which hurt the feeling and wound the soul. They pretend with open voice that Palestine, which is the Holy Land of our fathers and the graveyard of our ancestors, which has been inhabited by the Arabs for long ages, who loved it and died in defending it, is now a national home for them … We Arabs, Muslim and Christian, have always sympathized profoundly with the persecuted Jews and their misfortunes in other countries … but there is wide difference between such sympathy and the acceptance of such a nation … ruling over us and disposing of our affairs.[257]

The group also protested the carrying of new “white and blue banners with two inverted triangles in the middle”,[258] drawing the attention of the British authorities to the serious consequences of any political implications in raising the banners.[258] Later that month, on the first anniversary of the occupation of Jaffa by the British, the Muslim-Christian Association sent a lengthy memorandum and petition to the military governor protesting once more any formation of a Jewish state.[259] The majority of Britain’s military leaders considered Balfour’s declaration either a mistake, or one that presented grave risks.[260]

Broader Arab response

In the broader Arab world, the declaration was seen as a betrayal of the British wartime understandings with the Arabs.[243] The Sharif of Mecca and other Arab leaders considered the declaration a violation of a previous commitment made in the McMahon–Hussein correspondence in exchange for launching the Arab Revolt.[90]

Following the publication of the declaration in an Egyptian newspaper, Al Muqattam,[261] the British dispatched Commander David George Hogarth to see Hussein in January 1918 bearing the message that the “political and economic freedom” of the Palestinian population was not in question.[80] Hogarth reported that Hussein “would not accept an independent Jewish State in Palestine, nor was I instructed to warn him that such a state was contemplated by Great Britain”.[262] Hussein had also learned of the Sykes–Picot Agreement when it was leaked by the new Soviet government in December 1917, but was satisfied by two disingenuous messages from Sir Reginald Wingate, who had replaced McMahon as High Commissioner of Egypt, assuring him that the British commitments to the Arabs were still valid and that the Sykes–Picot Agreement was not a formal treaty.[80]

Continuing Arab disquiet over Allied intentions also led during 1918 to the British Declaration to the Seven and the Anglo-French Declaration, the latter promising “the complete and final liberation of the peoples who have for so long been oppressed by the Turks, and the setting up of national governments and administrations deriving their authority from the free exercise of the initiative and choice of the indigenous populations”.[80][263]

In 1919, King Hussein refused to ratify the Treaty of Versailles. After February, 1920, the British ceased to pay subsidy to him.[264] In August 1920, five days after the signing of the Treaty of Sèvres, which formally recognized the Kingdom of Hejaz, Curzon asked Cairo to procure Hussein’s signature to both treaties and agreed to make a payment of £30,000 conditional on signature.[265] Hussein declined and in 1921, stated that he could not be expected to “affix his name to a document assigning Palestine to the Zionists and Syria to foreigners.”[266] Following the 1921 Cairo Conference, Lawrence was sent to try and obtain the King’s signature to a treaty as well as to Versailles and Sèvres, a £60,000 annual subsidy being proposed; this attempt also failed.[267] During 1923, the British made one further attempt to settle outstanding issues with Hussein and once again, the attempt foundered, Hussein continued in his refusal to recognize the Balfour Declaration or any of the Mandates that he perceived as being his domain. In March 1924, having briefly considered the possibility of removing the offending article from the treaty, the government suspended any further negotiations;[268] within six months they withdrew their support in favour of their central Arabian ally Ibn Saud, who proceeded to conquer Hussein’s kingdom.[269]

Allies and Associated Powers

The declaration was first endorsed by a foreign government on 27 December 1917, when Serbian Zionist leader and diplomat David Albala announced the support of Serbia’s government in exile during a mission to the United States.[270][271][272][273] The French and Italian governments offered their endorsements, on 14 February and 9 May 1918, respectively.[274] At a private meeting in London on 1 December 1918, Lloyd George and French Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau agreed to certain modifications to the Sykes-Picot Agreement, including British control of Palestine.[275]

On 25 April 1920, the San Remo conference – an outgrowth of the Paris Peace Conference attended by the prime ministers of Britain, France and Italy, the Japanese Ambassador to France, and the United States Ambassador to Italy – established the basic terms for three League of Nations mandates: a French mandate for Syria, and British mandates for Mesopotamia and Palestine.[276] With respect to Palestine, the resolution stated that the British were responsible for putting into effect the terms of the Balfour Declaration.[277] The French and the Italians made clear their dislike of the “Zionist cast of the Palestinian mandate” and objected especially to language that did not safeguard the “political” rights of non-Jews, accepting Curzon’s claim that “in the British language all ordinary rights were included in “civil rights””.[278] At the request of France, it was agreed that an undertaking was to be inserted in the mandate’s procès-verbal that this would not involve the surrender of the rights hitherto enjoyed by the non-Jewish communities in Palestine.[277] The Italian endorsement of the Declaration had included the condition “… on the understanding that there is no prejudice against the legal and political status of the already existing religious communities …” (in Italian “… che non ne venga nessun pregiudizio allo stato giuridico e politico delle gia esistenti communita religiose …”[279] The boundaries of Palestine were left unspecified, to “be determined by the Principal Allied Powers.”[277] Three months later, in July 1920, the French defeat of Faisal’s Arab Kingdom of Syria precipitated the British need to know “what is the ‘Syria’ for which the French received a mandate at San Remo?” and “does it include Transjordania?”[280] – it subsequently decided to pursue a policy of associating Transjordan with the mandated area of Palestine without adding it to the area of the Jewish National Home.[281][282]

In 1922, Congress officially endorsed America’s support for the Balfour Declaration through the passage of the Lodge–Fish Resolution,[143][283][284] notwithstanding opposition from the State Department.[285] Professor Lawrence Davidson, of West Chester University, whose research focuses on American relations with the Middle East, argues that President Wilson and Congress ignored democratic values in favour of “biblical romanticism” when they endorsed the declaration.[286] He points to an organized pro-Zionist lobby in the United States, which was active at a time when the country’s small Arab American community had little political power.[286]

Central Powers

The publication of the Balfour Declaration was met with tactical responses from the Central Powers;[287] however the participation of the Ottoman Empire in the alliance meant that Germany was unable to effectively counter the British pronouncement.[288][ao]

Two weeks following the declaration, Ottokar Czernin, the Austrian Foreign Minister, gave an interview to Arthur Hantke, President of the Zionist Federation of Germany, promising that his government would influence the Turks once the war was over.[289] On 12 December, the Ottoman Grand Vizier, Talaat Pasha, gave an interview to the German newspaper Vossische Zeitung[289] that was published on 31 December and subsequently released in the German-Jewish periodical Jüdische Rundschau on 4 January 1918,[290][289] in which he referred to the declaration as “une blague”[289] (a deception) and promised that under Ottoman rule “all justifiable wishes of the Jews in Palestine would be able to find their fulfilment” subject to the absorptive capacity of the country.[289] This Turkish statement was endorsed by the German Foreign Office on 5 January 1918.[289] On 8 January 1918, a German-Jewish Society, the Union of German Jewish Organizations for the Protection of the Rights of the Jews of the East (VJOD),[ap] was formed to advocate for further progress for Jews in Palestine.[291]

Following the war, the Treaty of Sèvres was signed by the Ottoman Empire on 10 August 1920.[292] The treaty dissolved the Ottoman Empire, requiring Turkey to renounce sovereignty over much of the Middle East.[292] Article 95 of the treaty incorporated the terms of the Balfour Declaration with respect to “the administration of Palestine, within such boundaries as may be determined by the Principal Allied Powers”.[292] Since incorporation of the declaration into the Treaty of Sèvres did not affect the legal status of either the declaration or the Mandate, there was also no effect when Sèvres was superseded by the Treaty of Lausanne, which did not include any reference to the declaration.[293]

In 1922, German anti-Semitic theorist Alfred Rosenberg in his primary contribution to Nazi theory on Zionism,[294] Der Staatsfeindliche Zionismus (“Zionism, the Enemy of the State”), accused German Zionists of working for a German defeat and supporting Britain and the implementation of the Balfour Declaration, in a version of the stab-in-the-back myth.[xxix] Adolf Hitler took a similar approach in some of his speeches from 1920 onwards.[295]

The Holy See

Further information: Pope Benedict XV and JudaismWith the advent of the declaration and the British entry into Jerusalem on 9 December, the Vatican reversed its earlier sympathetic attitude to Zionism and adopted an oppositional stance that was to continue until the early 1990s.[296]

Evolution of British opinion

“It is said that the effect of the Balfour Declaration was to leave the Moslems and Christians dumbfounded … It is impossible to minimise the bitterness of the awakening. They considered that they were to be handed over to an oppression which they hated far more than the Turk’s and were aghast at the thought of this domination … Prominent people openly talk of betrayal and that England has sold the country and received the price … Towards the Administration [the Zionists] adopted the attitude of “We want the Jewish State and we won’t wait”, and they did not hesitate to avail themselves of every means open to them in this country and abroad to force the hand of an Administration bound to respect the “Status Quo” and to commit it, and thereby future Administrations, to a policy not contemplated in the Balfour Declaration … What more natural than that [the Moslems and Christians] should fail to realise the immense difficulties the Administration was and is labouring under and come to the conclusion that the openly published demands of the Jews were to be granted and the guarantees in the Declaration were to become but a dead letter?”

Report of the Palin Commission, August 1920[297]

The British policy as stated in the declaration was to face numerous challenges to its implementation in the following years. The first of these was the indirect peace negotiations which took place between Britain and the Ottomans in December 1917 and January 1918 during a pause in the hostilities for the rainy season;[298] although these peace talks were unsuccessful, archival records suggest that key members of the War Cabinet may have been willing to permit leaving Palestine under nominal Turkish sovereignty as part of an overall deal.[299]

In October 1919, almost a year after the end of the war, Lord Curzon succeeded Balfour as Foreign Secretary. Curzon had been a member of the 1917 Cabinet that had approved the declaration, and according to British historian Sir David Gilmour, Curzon had been “the only senior figure in the British government at the time who foresaw that its policy would lead to decades of Arab–Jewish hostility”.[300] He therefore determined to pursue a policy in line with its “narrower and more prudent rather than the wider interpretation”.[301] Following Bonar Law‘s appointment as Prime Minister in late 1922, Curzon wrote to Law that he regarded the declaration as “the worst” of Britain’s Middle East commitments and “a striking contradiction of our publicly declared principles”.[302]

In August 1920 the report of the Palin Commission, the first in a long line of British Commissions of Inquiry on the question of Palestine during the Mandate period,[303] noted that “The Balfour Declaration … is undoubtedly the starting point of the whole trouble”. The conclusion of the report, which was not published, mentioned the Balfour Declaration three times, stating that “the causes of the alienation and exasperation of the feelings of the population of Palestine” included:

- “inability to reconcile the Allies’ declared policy of self-determination with the Balfour Declaration, giving rise to a sense of betrayal and intense anxiety for their future”;[304]

- “misapprehension of the true meaning of the Balfour Declaration and forgetfulness of the guarantees determined therein, due to the loose rhetoric of politicians and the exaggerated statements and writings of interested persons, chiefly Zionists”;[304] and

- “Zionist indiscretion and aggression since the Balfour Declaration aggravating such fears”.[304]

British public and government opinion became increasingly unfavourable to state support for Zionism; even Sykes had begun to change his views in late 1918.[aq] In February 1922 Churchill telegraphed Samuel, who had begun his role as High Commissioner for Palestine 18 months earlier, asking for cuts in expenditure and noting:

In both Houses of Parliament there is growing movement of hostility, against Zionist policy in Palestine, which will be stimulated by recent Northcliffe articles.[ar] I do not attach undue importance to this movement, but it is increasingly difficult to meet the argument that it is unfair to ask the British taxpayer, already overwhelmed with taxation, to bear the cost of imposing on Palestine an unpopular policy.[307]

Following the issuance of the Churchill White Paper in June 1922, the House of Lords rejected a Palestine Mandate that incorporated the Balfour Declaration by 60 votes to 25, following a motion issued by Lord Islington.[308][309] The vote proved to be only symbolic as it was subsequently overruled by a vote in the House of Commons following a tactical pivot and variety of promises made by Churchill.[308][xxx]

In February 1923, following the change in government, Cavendish, in a lengthy memorandum for the Cabinet, laid the foundation for a secret review of Palestine policy:

It would be idle to pretend that the Zionist policy is other than an unpopular one. It has been bitterly attacked in Parliament and is still being fiercely assailed in certain sections of the press. The ostensible grounds of attack are threefold:(1) the alleged violation of the McMahon pledges; (2) the injustice of imposing upon a country a policy to which the great majority of its inhabitants are opposed; and (3) the financial burden upon the British taxpayer …[312]

His covering note asked for a statement of policy to be made as soon as possible and that the cabinet ought to focus on three questions: (1) whether or not pledges to the Arabs conflict with the Balfour declaration; (2) if not, whether the new government should continue the policy set down by the old government in the 1922 White Paper; and (3) if not, what alternative policy should be adopted.[154]

Stanley Baldwin, replacing Bonar Law as Prime Minister, in June 1923 set up a cabinet sub-committee whose terms of reference were:

examine Palestine policy afresh and to advise the full Cabinet whether Britain should remain in Palestine and whether if she remained, the pro-Zionist policy should be continued.[313]