Home › Forums › JUST A RANT › Answering 13 questions about the Index of Race Law written by Martin van Staden

- This topic is empty.

Viewing 1 post (of 1 total)

-

AuthorPosts

-

2025-03-20 at 17:32 #464163

Nat QuinnKeymaster

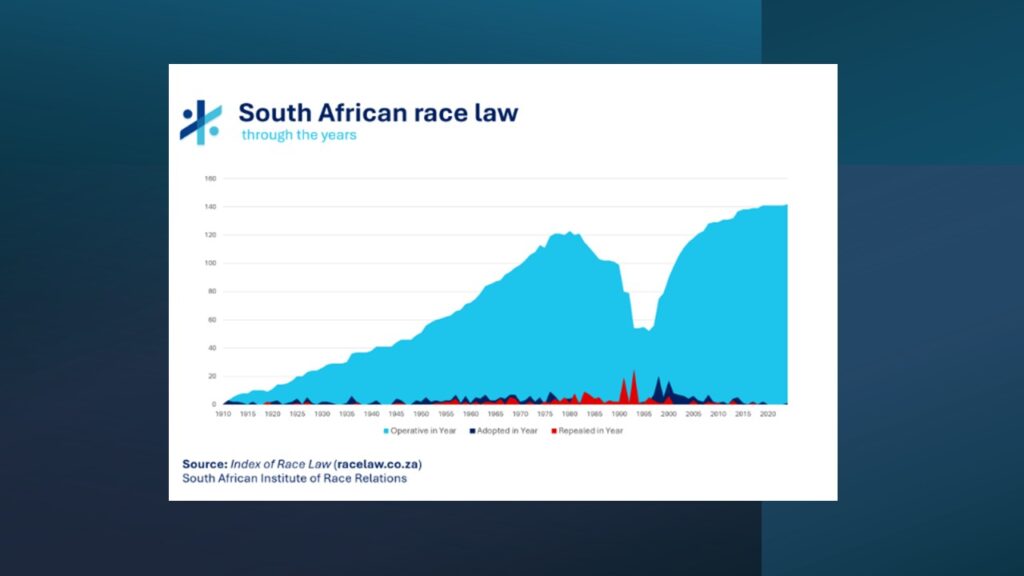

Nat QuinnKeymasterThe Index of Race Law was launched to little fanfare in December 2022 by the Institute of Race Relations (IRR), as the only up-to-date and comprehensive record of legislated racial discrimination in South Africa. Due in large part to AfriForum and Solidarity popularising it throughout 2024, and Donald Trump and Elon Musk noting it in 2025, the Index has suddenly gained a lot of attention. This is to be welcomed.

As the compiler and chief researcher behind the Index, I am taking the opportunity to answer some questions and address some controversies about it.

Acknowledgements

First, some credit where it is due.

Kaitlin Rawson and “Cthulhucachoo” are the only two critics of the Index of Race Law who rolled up their sleeves and put in some actual work to determine whether the Index is credible or “propaganda.” While they seem to still conclude that it is the latter, their work output comes incredibly close to affirming the current state of research evident in the Index.

So thorough is some of their work, that I will partly rely on it to inform the next updates to the Index to bring about more clarity and specificity.

While other critics – even ostensible lawyers like Thuli Madonsela – screech about vibes and feelings, these two non-lawyers did the lawyerly thing and actually inquired into the reality of things. This is how fact-checking should work.

I certainly do not appreciate their construing the Index as a malicious tool of propaganda, but I must thank them – sincerely – for what appears to be good-faith and serious engagement.

Dan Corder, on the other hand, did not through blood alone inherit lawyerly instincts but decided to make a fool of himself anyway.

The way he approached his task was brazenly malicious and mocking. I only acknowledge his “work” because, to the degree that he did engage, he also ended up affirming the factual (but not vibey) accuracy of the Index.

The one glaring inaccuracy in Corder’s “analysis” is his reference to the Labour Relations Act. He notes that the Act was included in the Index because it prohibits racial discrimination by trade unions, employers, and employers’ organisations.

This is false, and he should know it is false, because it does not satisfy the definition of race law as expounded by the Index.

Instead, sections 115 and 117 of the Labour Relations Act, which allows the CCMA to help employers implement “affirmative action” programmes – the opposite of prohibiting racial discrimination – and require that the CCMA be racially reflective of South Africa’s demographics, respectively, are the reasons for including the Act.

Jonathan Wright and Garth Schoeman are also thanked for bringing to my attention racial Acts of Parliament from the pre-1994 era that were missed. These have all been verified and included in the Index.

1. Anthony (@TheWriteAnt) on X asks: “What defines what a race law is and what classification is used to be included here?”

“Race law” is defined descriptively rather than normatively. Many laypersons approach it normatively, arguing that “if it is a good law, or a law I like, it cannot be a race law.” That approach is rejected, in favour of the standard of “if the law keeps or makes a person’s race or skin-colour legally relevant, or allows a minister, official, or body to keep or make it relevant, it is a race law.”

That is the definition that triggers inclusion in the Index.

There are and will, of course, be some edge cases.

The Expropriation Act of 2024 makes no explicit reference to race, but in time we might see that its “public interest” criterion is racially enforced like how “previously disadvantaged” or “disadvantaged by unfair discrimination” from other laws are. Is this then a race law? That question has not been decisively answered yet, but at some juncture a decision will need to be made.

2. Anthony (@TheWriteAnt) on X asks: “Where do you source these laws that form the index?”

Wikipedia has a list of all the Acts that the South African Parliament has ever adopted. This list is not always accurate, but it is a useful starting point.

From there, I have utilised search functions in legislation databases like Sabinet to detect whether stock-standard legislative racial terminology appears in the Acts.

For pre-1994 laws, it would usually be something along the lines of “native,” “Bantu,” “black,” “white,” “non-white,” “European,” “non-European,” “Asian,” “Malay,” “community development,” “group,” and “population.”

For post-1994 laws, it would usually be something like “black,” “previously” or “historically disadvantaged” or “disadvantaged by unfair discrimination,” “race” or “racial,” “representative,” “representivity,” “transformation,” “equity,” “equitable,” “demographic,” “redress,” and “past injustices.”

If Sabinet says that these terms appear in a legal text, I open the Act’s text and verify that the provision it has detected is in fact a racial provision and not some innocuous provision wherein the word “black,” “white,” or “race” appears in a different context.

This means that those Acts that the search database does not detect for whatever reason (like the Defence Act of 1957 and Expropriation Act of 1975) will be missed, and this is where the Index relies upon other eagle-eyed analysts, researchers, and laypersons to help fill the gaps.

3. Anthony (@TheWriteAnt) on X asks: “Are these laws congregated in a particular area of law or is it spread out over the whole scope of SA law?”

In terms of substantive law, the Index covers the entire field of South African law, but with the important proviso that only one source of law is currently included: Acts of Parliament.

Acts of Provincial Legislatures, municipal bylaws, regulations in all three spheres of government, and judicial precedent – all qualifying as “law” – are not presently included in the Index. The plan is for the Index to cover all sources of law in the (distant) future.

(This does mean, it must be noted, that the number of race laws applicable in South Africa is certainly far higher than the ~140 Acts of Parliament.)

4. Anthony (@TheWriteAnt) on X asks: “Is there some scale in how severe or overt the race law is or is it only the binary of yes, it is or no it’s not a race law?”

The binary of “race law” or “not race law” is what the Index utilises.

While the IRR and I do have a normative perspective on race law per se, the Index of Race Law is meant to be a neutral resource. The Index (the table, the dataset) does not explicitly or implicitly pass judgment on whether a given law is good, bad, beneficial, detrimental, severe, or innocuous. The only task it has is to quantify the extent of race as a legislated phenomenon in South Africa.

Like all indices, it is meant to be a resource for future researchers with their own agendas to conduct further inquiry – for example, into the severity (or not) of particular race laws.

5. Kaitlin Rawson (@KaitlinRawson) on X asks: “Why are 9 deracialised laws counted among the 142 active race laws in SA?”

This is a technical question with a technical answer.

The Index records the total number of race laws ever adopted by the South African Parliament (currently 319).

The Index further records whether, of these race laws (that is, that have ever been adopted by Parliament), how many have been repealed or remain operative. Here, 142 remain operative. In other words, of all the Acts of Parliament that have ever been adopted, 319 were racial, and 142 of those remain operative.

This, of course, counts even those that have since been deracialised.

Realising that this could cause confusion, from the start the Index included the Deracialised category that Rawson usefully relies on, to enable readers to get the full picture. All the pertinent information is available.

Cthulhucachoo’s claim on the earlier linked Substack post that the “IRR has backtracked” by acknowledging that some race laws have been deracialised is therefore opportunistic and incorrect: the Deracialised category has been present from the launch of the Index. The added footnote on the homepage is simply to further clarify what is already available in the Index as it stands.

As I said at an AfriForum conference on 13 May 2024, and reiterated at a Solidarity conference on 10 September, “If you try to engage with the Index, however, you have to do so holistically. Doing so half-heartedly might give you misimpressions of the reality of race law in South Africa.”

6. Kaitlin Rawson (@KaitlinRawson) on X asks: “Why is the National Environmental Management: Waste Act, 2008 included?”

For these next three questions, Rawson rightly wonders in her video why the Waste Act, Protected Areas Act, and the National Small Enterprises Act were included in the Index. Her confusion is understandable and speaks to a broader problem in access to law in South Africa, and has alerted me to an error in the Index.

It must be stated unequivocally that no law is included in the Index simply because a “racial-ish” word has been found through a Ctrl+F keyword search process. All provisions are (allowing, always, for error) verified as racial.

The Waste Act was, it appears, adopted as a non-racial Act in 2008 (which is the version of the Act that Rawson made use of). It was, however, thereafter racialised by the Waste Amendment Act of 2014.

The triggering provisions start with section 13A(2)(b), which provides that the “pricing strategy” that the Minister develops must include the funding of, among other things, “the re-use, recycling or recovery of waste in previously disadvantaged communities.”

Then, section 13A(3)(b)(iii), which provides that the pricing strategy may differentiate on the basis of “whether any previously disadvantaged group is impacted upon or derives any benefit therefrom.”

The Waste Act is also further racial by section 34I(4)(b), which provides that members of the Waste Management Bureau’s governing board must be appointed in part on the basis of “the need for appointing persons to promote representivity.” This final provision is law, though it has not yet come into operation.

The Waste Act will, in the next Index update, reflect as Racialised rather than originally Racial.

7. Kaitlin Rawson (@KaitlinRawson) on X asks: “Why is the National Environmental Management: Protected Areas Act, 2003 included?”

This Act was not included in the Index, like Rawson implies it was, because the words “diversity” (as in, “biological diversity”) and “race” (as in, plant species) appears in it.

This applies to the National Small Enterprise Act below as well, which Rawson also believes was only included because the word “white” (as in, “White Paper”) features in the legislative text.

The Protected Areas Act was included in the Index by virtue of section 59(4) of the Act, which provides that when the board of South African National Parks is appointed, the “need for appointing persons disadvantaged by unfair discrimination” must be taken into account.

This provision was added by the Protected Areas Amendment Act of 2004. The Act, in other words, appears to have originally been non-racial when it was adopted in 2003, which is the version of the Act that Rawson saw. The Index errantly records it as originally Racial, but this will be rectified as Racialised.

8. Kaitlin Rawson (@KaitlinRawson) on X asks: “Why is the National Small Enterprises Act included?”

The National Small Enterprises Act was originally adopted in 1996 as the National Small Business Act, which at the time was non-racial. This is the version of the Act that Rawson had sight of, and the version of the Act that the government makes available when you search for it online.

Now the interesting things regarding the Act begin to come out.

When the Index was constructed during the course of 2022, section 11 of the Act was titled “Constitution of Board and appointment of members of Board.” This provision was added by the 2004 amendment to the Act.

Section 11(4) in particular provided that the Minister must ensure the board “represents a broad cross-section of the population of South Africa and comprises persons who reflect the South African society with special attention to race, gender, disability, geographical spread, and organisations based in rural areas.”

The Act was included in the Index by virtue of this “representivity” provision.

Fast-forward to 2024, and section 11 is gone and replaced.

The Act no longer has “representivity” provisions relating to the governing structures of the Small Enterprise Development Finance Agency, but now has a whole raft of other racial provisions.

In terms of the National Small Enterprise Amendment Act of 2024, section 10(b) of the Act now obliges the Agency to promote “job creation and equity to historically disadvantaged communities”; section 13(c)(v) obliges the agency to “design and implement small enterprise development support programmes in order to promote participation of historically disadvantaged persons in small enterprises”; and section 19(1)(e) requires “statistical analysis of the contribution of […] the level of inclusion of previously disadvantaged groups into the economy.”

As with the Waste Act and Protected Areas Act, when this Act was initially analysed, it was missed that the racial provisions were only introduced subsequent to the Act’s adoption.

Many South Africans, including lawyers, err by not reading Acts together with their amendments. The state can solve this, very simply, by keeping Acts and amendments together and (re)publishing the complete law when it has been amended. This, of course, requires effort, which is not within the South African government’s frame of reference.

This state-induced confusion makes it all the more vital for the public to constructively point out any errors noticed.

The Index will be updated to reflect that the National Small Enterprise Act was subsequently Racialised rather than originally Racial.

To her credit, when speaking to all three Acts, Rawson said she might be missing something and was open to correction.

9. Kaitlin Rawson (@KaitlinRawson) on X asks: “Why is there a discrepancy on your desktop vs mobile version of the website in terms of the counter of the number of laws?”

This error has been corrected. I was unaware that WordPress requires one to update this specific widget separately for different platforms.

10. Kaitlin Rawson (@KaitlinRawson) on X asks: “What justifies including a law that only mentions representativity in one section of an entire act as a race law?”

The Republican Constitution of 1961 and Tricameral Constitution of 1983 both only made fleeting references to race, and spent the bulk of their texts going over rote matters of divisions of power and governance. These are, however, rightly regarded as foundational race laws.

If this were an Index of Legislative Protections for the LGBT Community, and, for instance, the Housing Act were to include a provision saying the state may not discriminate based on the sexual orientation of housing beneficiaries, such an index would have recorded the Housing Act, despite the fact that this would only have been one part of a far more comprehensive law.

To exclude laws from being recorded in an index of race law only on the basis that the racial provision represents a small part of the law, would make any recording race-in-law impossible. As with other considerations, I need to limit my own discretion in deciding whether a single reference to race is a “big” or a “small” feature of a given Act.

11. Kaitlin Rawson (@KaitlinRawson) on X asks: “Why have details of relevant sections not been made available yet? the index has been up for multiple years now.”

This is a question of capacity. As Rawson herself says in her video, analysing the specific provisions of each law is a “very tedious task, very tedious work” (and kudos to her for doing it). One pair of hands can only do so much, especially when it is a part-time endeavour.

Thankfully, every taxpaying South African and every citizen has the right to approach the government and request an updated copy of any and every Act of Parliament, especially those in force. The Index spells out precisely which laws are considered racial, and can be disproven at the drop of a hat if one feels so inclined.

As the compiler of the Index, I could not hide anything even if I wanted to.

Thankfully, Rawson’s own research into specific provisions, alongside research ostensibly done by Corder, appears to confirm that the Index – allowing for the odd mistake here and there – is accurate. I welcome the peer-review.

12. Kaitlin Rawson (@KaitlinRawson) on X asks: “Why are functionally obsolete laws included as active / operative race laws?”

It is important for me to limit my own discretion as far as I possibly and reasonably can – though I can never exclude it entirely.

This includes disallowing myself to decide which laws are and are not “functionally obsolete.” For me to deem a certain racial provision unenforceable because I do not think it is constitutionally complaint would mean that I could also deem the Employment Equity Act, B-BBEE Act, and many others, to be unenforceable because I regard them (as I do) to be unconstitutional.

The convention has been – and this has been observed in the supermajority of cases by all South Africa’s legislatures since 1910 – for Parliament to explicitly repeal those laws it no longer desires to see on the books. I have deferred to this convention.

13. Kaitlin Rawson (@KaitlinRawson) on X asks: “Why do you and the IRR not speak out when these laws are called discriminatory towards whit[e] people considering there are a number of pre-democratic laws in the index?”

The IRR has spoken out against race laws since 1929. It has done this because of an opposition to race law per se, regardless of who it ostensibly favours or disadvantages.

By constructing the Index – from the beginning including laws from before 1994 – the IRR and I have “spoken out.”

If our interest was only in propagandising the continued racialism evident in the post-1994 establishment, the Index could very well have only recorded the race laws of this constitutional dispensation (1994-present). But the decision was consciously made to look at race law as an historical and enduring South African phenomenon.

Nonetheless – and saying this should not be contentious – it should be obvious that virtually all of the race laws that are not “functionally obsolete” today and are in operation and are enforced, operate primarily against white individuals.

Whether this is severe or innocuous, or truly harmful or unintentionally beneficial to whites, is not in question: the only question is whether the law, which is supposed to be the common heritage of all bound by it, discriminates against or in favour of some legal subjects.

Of course, Rawson will want to debate me on this, and that is fine, but this is precisely why the Index of Race Law does not try to wade into the normative question of whether this law or that law “actually” benefits or harms anyone. The discourse is fraught as it is, and need not be complicated even further.

The Index looks only at whether a law is a race law, and leaves it at that. Other researchers can, and are encouraged to, utilise the Index as a starting point in their own journeys of inquiring into specific aspects of race law that interest them.

source:Answering 13 questions about the Index of Race Law – Daily Friend

-

AuthorPosts

Viewing 1 post (of 1 total)

- You must be logged in to reply to this topic.