Home › Forums › NATS NIBBLES › Hospital secrets: One in 17 Canadian patients harmed by mistakes that sometimes turn deadly

- This topic is empty.

Viewing 1 post (of 1 total)

-

AuthorPosts

-

2023-07-30 at 00:31 #414198

Nat QuinnKeymaster

Nat QuinnKeymasterOn a July afternoon in 2010, Anna Maria Fiocco, then 62, underwent surgery to fix a leaky heart valve. She woke up a paraplegic, the “unfortunate victim,” a judge would rule seven years later, “of a therapeutic accident.”

“Why am I like this?” Anna’s husband, Donald McKnight, remembers his wife asking the heart surgeon when she arrived in her wheelchair for her first follow-up appointment, three months post-op. “Things happen,” she was told, according to her family.

Primum non nocere, “above all, do no harm,” is an enduring and ancient medical ethic, though patient safety expert Darrell Horn has yet to meet a doctor or nurse — and he’s interviewed hundreds — who went to work one morning with the intent to purposely hurt someone.

But unintentional harm happens to tens of thousands of people every year in Canada’s hospitals, even though most provinces and territories aren’t publicly reporting “patient safety incidents,” including some of the most egregious. Life-threatening medication blunders, clamps, sponges or other “foreign bodies” left inside people after surgery, fatal bed sores from not mobilizing or turning patients that eat away at the underlying tissue, tunnelling down through layers of skin to expose the bone.

Nearly 20 years after a watershed report estimated that up to 23,750 people experience an adverse event and later die in Canada’s hospitals each year from preventable errors, mishaps and “clinical misadventures,” as they’re sometimes called, patient harm in hospitals remains a deadly threat.

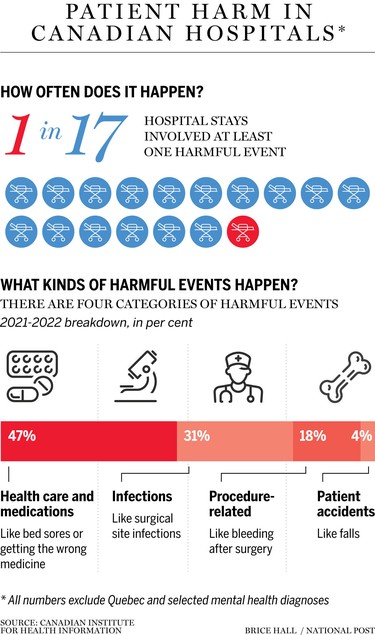

The true scale is unknown. One in 17 hospitalizations in 2021-22 — roughly 140,000 out of 2.4 million hospital stays — resulted in someone experiencing a harmful event signIficant enough to require treatment or a prolonged hospital stay, according to the Canadian Institute for Health Information. Pre-COVID, it was one in 18. But the statistics don’t tell the whole story. Harms in emergency rooms aren’t captured, nor are “near misses,” or harm due to a misdiagnosis, harms in rehab or mental care, or harms that start in hospital but aren’t detected until the person is sent home.

The numbers are also dry statistics with no details or voices, or human stories, save for the people who have lived that harm. Legal privilege laws intended to encourage hospital staff involved in critical incidents to speak freely and frankly in investigations without fear that what they say will be used against them are providing a formidable blanket of secrecy, patient safety advocates say. Victims are frequently denied “a full and robust explanation,” Horn and his colleagues recently reported, leaving surviving patients and families wondering months, even years later, “what happened?”

While hospitals are obligated to disclose that an error occurred, there’s considerable confusion around what “facts” should be shared with families at the end of an incident review — or even what constitutes preventable harm. Across Canada, there’s no consensus “on the terminology, categorization or tracking” of events across the country, researchers have reported.

“Very, very seldom will a family leave a hospital after a loved one passes knowing that a medical error has even occurred,” said Horn, who has investigated critical incidents across Canada.

Interviews with staff are for the purpose of an investigation only, and unless rare criminal conduct is detected — and there’s very, very little criminal activity in any of this, Horn said — it’s all under the umbrella of privilege. “Nothing the nurses or doctors tell (investigators) about what happened that day will ever be made public.”

Very, very seldom will a family leave a hospital after a loved one passes knowing that a medical error has even occurred

DARRELL HORNWhile people have sued hospitals and doctors for botched surgeries, or misdiagnosing a life-altering stroke in a 40-year-old man as vertigo, few have the financial or emotional wherewithal to go up against hospital insurers or the Canadian Medical Protective Association, a defence fund for doctors and whose membership premiums are heavily subsidized by taxpayers — “the patients themselves,” as researchers have noted. CMPA lawyers have been accused of pursuing a “scorched earth policy” in defending doctors accused of negligent medical care, though the CMPA will recommend settlement if faced with the hopelessly indefensible. Over the last 10 years, the fund has paid a total of $2.29 billion in patient compensation.

Few cases of hospital harm involve true negligence, a breach in the standard or duty of care. And not every preventable harm warrants a Swiss Air style investigation, Horn said. “But there’s a total lack of transparency in the system.”

It might be common parlance now, but “patient safety” wasn’t a term commonly used, outside a smattering of researchers, until the Baker-Norton study that found Canadian hospitals are risky places.

Dr. Ross Baker and Dr. Peter Norton were frustrated that a seminal American report published in 1999, To Err is Human, that estimated as many as 98,000 Americans died each year because of preventable medical mistakes, and called for sweeping changes to make hospitals safer, was having no impact in Canada. “We realized — and it’s hard to believe this — that people thought, ‘well, this is just another flaw in the American system, and we don’t have to worry about that,’” Baker said.

Twenty years out, Baker worries too little has been done to move the needle, and that too much secrecy still shrouds preventable harms.

“I worry that we have not spent the time and resources in recent years to make a difference, and that we are giving up the opportunity to really reduce the harm that occurs in health care,” said Baker, a professor emeritus at the University of Toronto’s Dalla Lana School of Public Health.

Hospitals in the U.S. face greater public scrutiny. There’s less transparency in Canada, Baker said. “I don’t think politicians want to see this.

“One of the downsides of a publicly funded, publicly administered system is that there’s a political element to it — politicians feel they’ll be beaten up if there are too many reports about problems in the system.”

A Strained System

Rates of burnout have never been higher. A hollowed-out health-care workforce, high turnover, overrun emergency rooms, a crushing backlog of surgeries shelved during COVID shutdowns. All have sapped a system that was already strained long before SARS-CoV-2 hit, and the higher the stress levels, the more dangerous hospitals become.

Article content

“There are areas where we have made fundamental changes in patient safety that influence our lives,” said Jennifer Zelmer, president of Healthcare Excellence Canada. Her grandmother was infected with liver-destroying hepatitis through a blood transfusion before Canada began screening blood. “The risk that I would be infected if I had the same surgery today is fundamentally different.”

Hospital care has gotten seriously more complex. “The folks in hospital now tend to have chronic conditions, tend to be older, and those are risk factors for harm,” Zelmer said. “If you’re on 10 medications, the chances that there’s going to be a medication mix-up is higher than if you’re on one.”

Protocols have been developed to try to reduce errors, like surgical checklists, a series of simple steps teams run through to make sure it’s the right person on the gurney, the right side of the body has been marked, that the area has been clipped and not shaved to prevent tiny micro-cuts on the skin and keep bacteria from seeping into surgical incisions. None of this is rocket science, Baker said, but there are people alive today who wouldn’t otherwise be, without such protocols, he said. Even then, “getting people to change their practice is sometimes very difficult.” Some surgeons think checklists are a waste of time.

Not all adverse events are preventable, Baker stressed. Just over a third were judged preventable in the Baker-Norton report. Bad outcomes happen in even excellent hospitals. But even harms once considered a “complication” of doing business, like hospital-acquired infections, are now seen as largely avoidable.

‘Never Events’

Still, even “never events” — entirely preventable critical incidents that should never happen under any circumstance — keep happening in every jurisdiction of the country. A cancer patient is given ten times the intended dose of hydromorphone, an opioid pain killer five to seven times more potent than morphine, after the hydromorphone is mistakenly drawn from a higher-concentration vial. A 15-year-old with a relatively common heart condition suffers a near-fatal burn while undergoing a cardiac ablation treatment. Ontario’s auditor general reported that, between 2015 and 2019, 10 of 15 “never events” identified by patient and health-care groups occurred at least 214 times at six of the 13 hospitals auditors reviewed. None of the six hospitals set any targets in their plans to stop never events from happening again.

Human Endeavour

Doctors and nurses aren’t omniscient. People make mistakes. Aviation, nuclear power — high-risk industries got safer by designing out a large part of the human element, Baker said. “You can’t do that in health care. Health care is a human endeavour.” And serious or deadly mishaps are rarely caused by the actions of one single human being. In fact, most of the time it’s a flawed system that sets staff up for failure, Baker said. Medication errors, wrong-side surgery, hospital-acquired bugs, falls, burns, sepsis, bed sores — almost always result from a chain reaction, a failure of the system at multiple stages that makes it difficult to provide proper care. “We are putting people into systems that are struggling to support what (health-care providers) were trained to do, and what they want to do,” Baker said.

Eight of 13 provinces and territories have laws mandating that adverse events be reported. But when Baker and his colleagues scanned the legislation, they found that mandatory reporting laws across the country “are generally designed to gather information about, rather than respond to and prevent patient safety incidents.”

There are also ways of “gaming” the system to produce artificially lower rates. For example, if the person was elderly, or had a bundle of complex health problems, wouldn’t he or she have died anyway? Should a “near miss” — a potentially lethal medication mix-up caught before the loaded syringe reached the patient — count?

What we see, a lot, is an attempt after the fact to create an alternative explanation for the patient’s bad outcome

DUNCAN EMBURY, MALPRACTICE LAWYER“What we see, a lot, is an attempt after the fact to create an alternative explanation for the patient’s bad outcome and focus all kinds of energy and time trying to prove some rare esoteric medical condition to deflect blame from the actual error that occurred and the harm that it caused,” said Toronto medical malpractice lawyer Duncan Embury. It’s a cycle of secrecy and deflection, he said, that’s bad for patient care.

No organization in the world is capable of rigorous self-examination, Horn and his colleagues argued. “If Air Canada crashes a plane, we don’t ask Air Canada to investigate. We’ve gotten a little bit better in policing — if a guy gets shot, they have an independent review.”

“In a hospital, you investigate yourself.”

With few exceptions, most cases of significant, preventable harm involve a breakdown in communication. Information doesn’t get passed along from nurses to doctors or vice versa. A nurse leaving her shift forgets to chart that she’s given the patient a scheduled narcotic. Near disasters have ensued when instructions were misheard because of background music in the operating room. “This whole Mozart-effect thing — there’s no foundation in science for it,” Horn said. “You don’t turn on Johnny Cash to land your 747.” In aviation, it’s known as the sterile cockpit rule — pilots can’t chitchat during take offs and landings. “In critical phases, 100 per cent attention is required,” Horn said.

You can’t measure what isn’t captured and most health-care providers still don’t feel safe raising safety issues. Hierarchies in medicine and hospitals keep junior staff from speaking up when they see mistakes happening.

“Nothing provides an incentive for change than to be involved in an event that turns out to have been preventable. It’s heart-rendering,” Baker said. “But if people don’t feel that they have to report these events, and if they feel they’re going to be blamed without a full investigation of all the causes, then you can’t make progress on this.”

Without progress, people will keep dying. Someone who experiences at least one harm in hospital is four times more likely to die than someone who doesn’t, according to CIHI, which does publicly report patient safety “indicators” by hospital, like rates of sepsis, or trauma during childbirth. CIHI also measures hospital harms by reviewing patient discharge records — if the person was treated for a bed sore, it’s highly unlikely they arrived with one.

Public Awareness

More public reporting could help, Baker said. The greater the public awareness, the greater the pressure to do things differently. Harmed patients or their families might very well demand compensation from the hospital, other observers have noted. “It might all seem terribly unfair to hospitals,” David Goldhill, author of Catastrophic Care: Why Everything We Think We Know about Health Care is Wrong, wrote in the New York Times. “But to a patient who trusts his life and well-being to a hospital, having a foreign object left in her body after surgery can result in pain, additional treatment and even death. And doesn’t that seem — what’s the word — unfair?”

Stories of alleged egregious errors often only come to public light through the media: The family of a 12-year-old Grande Prairie, Alberta girl,who had both legs amputated below the knee when she was 11 months old, as well as her right hand and three fingers on her left, allege that the hospital and doctors involved in her care misdiagnosed her bacterial lung infection, which developed into sepsis and septic shock (the hospital and Alberta Health Services reached an out-of-court settlement in a separate suit, CBC reports, but the defendant doctors have contested the allegation that they provided poor care, and the family’s $31.7 million lawsuit is under reserve with the trial judge).

Wendy Nicklin is a member of Patients for Patient Safety Canada, a group of individuals or their families who have either experienced harm during care or are still living it. “We all compare our stories and it’s not uncommon that the health-care organization is just not forthcoming on exactly what did happen,” said Nicklin, a former senior hospital executive with an extensive background in critical care nursing and leadership.

“Is it fear of how the family will react? Fear something will be misinterpreted? If there’s honest, open, transparent communication, that goes a long way.” It won’t reverse the harm, she said. But it will help the healing.

“And everyone wants an apology, Nicklin said. “It doesn’t mean to imply guilt. But there needs to be an apology. There was no apology in my family’s case. Zero apology.” Anna Maria Fiocco was her sister-in law.

Anna, a bright, gregarious, positive businesswoman with an MBA, a lifelong volunteer who was devoted to her three children and family, had a heart issue. Three of the four valves that control blood flow through the heart weren’t in great condition, the mitral valve the worst.

It’s not clear what went wrong, but when Anna was taken into surgery for mitral valve repair and her chest opened, the surgeon realized he’d have to replace the valve, not repair it. The new mechanical valve had to be removed and installed a second time. At some point, Anna suffered a heart attack. Almost immediately after surgery, she went into cardiac arrest. She was resuscitated after 40 minutes. “Thankfully, her brain was fine,” Nicklin said. But when Anna woke from a medically induced coma, three days post-op, she couldn’t move her legs. “She could wiggle her toes, that was the weird thing,” Donald said. “But it never went beyond that.”

It was thought she may have suffered spinal cord hypoxia, an insufficient blood supply to the spinal cord when her heart stopped, but the cause was never definitely determined. While Anna’s life had been “forever transformed,” the judge could not establish fault on the part of the doctor.

There was no apology in my family’s case. Zero apology

WENDY NICKLIN, ANNA’S SISTER IN-LAWAnna and Donald had to move out of their two-storey home and into a wheel-chair accessible condominium. Frustrated by a lack of answers and explanations from the hospital and doctors, the family sued. “We went the full nine yards, and we lost,” Nicklin said. They also incurred more than $200,000 in legal fees. Unlike countries such as New Zealand, Canada doesn’t have a no-fault compensation scheme for medical mishaps. With no-fault health insurance, the family would at least have received some financial renumeration.

Anna died last year at 73. People with spinal cord injuries are prone to recurring urinary tract infections. The last bout in her bladder spread to Anna’s blood. She spent five weeks in hospital before dying of sepsis.

“If she wasn’t a feisty Italian, I don’t know that she would have done as well as she did,” Nicklin said. “She was in her wheelchair all the time and, bless her heart, after two or three years she said, ‘I’m not angry. This is my fate, and I will make the most of it.’

“The Superior Court judge stated that the surgeon had tried his best, that things happen, and that this was unfortunate,” Nicklin said. “And that was it. That was it.”

Ontario legislation requires that systems be in place to ensure every critical incident is disclosed to the patient (or, if the person has died, to their estate trustee) as soon as possible, as well as any “systematic steps being taken or that have been taken to reduce the risk of similar critical incidents occurring in the future,” Dale said in an email to the National Post.

In some cases, the incident is referred for review by a quality-of-care committee, reviews that are protected from “certain disclosures,” Dale said, so that frontline staff can speak freely about their “observations, perceptions and opinions in order to establish the circumstances of an incident and identify lessons learned.”

Dale added: “Even in these cases, while the details of the review may not be shared, patients and their families are always provided with the facts of the incident and steps taken by the hospital.”

Most people say, ‘I’ve got the best doctors, I’ve got the best nurses.’ But there are others who say, ‘they killed my mother’

DARRELL HORNHorn remains skeptical. Serious incidents should be reviewed by an independent third-party agency that makes its reports public, he said “so that people have real confidence.”

“Find somebody who has been in Canada for at least 10 or 20 years who doesn’t know somebody who was harmed in health care. Everybody does,” Horn said.

“Most people say, ‘I’ve got the best doctors, I’ve got the best nurses.’ But there are others who say, ‘they killed my mother.’”

“Everybody has that thing about, ‘We’re going to look into this, we’re going to learn everything we can from this to make sure it never happens again.’ It doesn’t happen,” Horn said. “It’s just a way of kicking the can.”

source:Canada’s hospital secrets: The deadly mistakes they keep making | National Post

-

AuthorPosts

Viewing 1 post (of 1 total)

- You must be logged in to reply to this topic.