Home › Forums › JUST A RANT › Objective journalism should be defended

- This topic is empty.

Viewing 1 post (of 1 total)

-

AuthorPosts

-

2023-03-03 at 18:56 #395858

Nat QuinnKeymaster

Nat QuinnKeymasterA most alarming trend in 21st-century journalism has been to reject objectivity in favour of activist journalism. It only serves to polarise and confuse news consumers.

‘Objectivity has got to go,’ Emilio Garcia-Ruiz, editor in chief of the San Francisco Chronicle, told the Washington Post.

The basis of this view is that standards for objectivity are themselves the product of opinion and is usually dictated by the establishment – that is, people who are largely older, largely white, largely male, largely heterosexual.

‘The consensus among younger journalists is that we got it all wrong,’ Emilio Garcia-Ruiz said.

The Washington Post article, written by Leonard Downie Jr., a former executive editor of the Post, and professor at the Walter Cronkite School of Journalism and Mass Communication at Arizona State University, cannot be easily dismissed as mere opinion.

It is the product of very extensive research, and more than 75 interviews to discover the ‘values and practices in mainstream newsrooms today’.

‘What we found has convinced us that truth-seeking news media must move beyond whatever “objectivity” once meant to produce more trustworthy news,’ Downie wrote. ‘This appears to be the beginning of another generational shift in American journalism.’

Cronkite

Yet, as he also points out, this is hardly a new idea.

Anti-establishment journalism was a prominent feature of the counter-culture of the 1960s and 1970s. Critical reporting on Watergate and the Vietnam War broke the mould, and remain legendary milestones to this day.

Yet that was also the era when, as (over-simplified) legend has it, Walter Cronkite single-handedly lost the Vietnam War by uttering these famous words on national television: ‘For it seems now more certain than ever, that the bloody experience of Vietnam is to end in a stalemate.’

That a single journalist, even an anchor of the stature of Cronkite, could possibly have surveyed the war in sufficient depth to predict its outcome and declare it over is, of course, ridiculous.

Yet his influence on public opinion did turn the tide and signalled the beginning of the end of a war that the US never militarily lost but had to disengage from because of growing domestic resistance.

It was a victory of subjectivity over objectivity.

Yet Cronkite himself, in the last decade of his life, advised journalists to ‘take a strong stand’ on matters such as the Iraq War, instead of remaining neutral reporters of verifiable facts.

Today, the impulse against journalistic objectivity comes from the left, and particularly, from the diversity and critical theory movement.

(By saying so, I don’t want to diminish the grave attacks on the media and free press from the right, where fake news is routinely broadcast while accusations of ‘fake news’ have been weaponised to stifle dissent from the left. But that’s not what Downie’s article is about.)

What is objectivity?

Downie relates that he never understood quite what objectivity meant: ‘Throughout the time, beginning in 1984, when I worked as [the Post’s Ben] Bradlee’s managing editor and then, from 1991 to 2008, succeeded him as executive editor, I never understood what “objectivity” meant. I didn’t consider it a standard for our newsroom. My goals for our journalism were instead accuracy, fairness, nonpartisanship, accountability and the pursuit of truth.’

I’d consider that an acceptable substitute for objectivity, since absolute objectivity is philosophically not even achievable in pure mathematics. (If you know the history of Kurt Gödel versus the positivists, you’ll understand why.)

‘More and more journalists of color and younger White reporters, including LGBTQ+ people, in increasingly diverse newsrooms believe that the concept of objectivity has prevented truly accurate reporting informed by their own backgrounds, experiences and points of view,’ wrote Downie.

I entirely accept that the experiences of marginalised people have struggled for airtime in the media. I welcome the publication of far more diverse viewpoints.

I do not believe that marginalisation is caused by objectivity, however. There is nothing preventing newspapers from publishing opinion from people of all walks of life and all backgrounds or reporting on statements by organisations all over the political and identitarian spectrum.

Rejecting the quest for objectivity in news reporting is to throw the baby out with the bathwater. I’d rather see all sides of issues approached without judgement, without fear or favour, and without partisan bias.

Critical theory

The real issue here can be traced back to critical theory (dense Marxist verbiage warning), which elevates ‘lived experiences’ and ‘other ways of knowing’ above objective facts and detached reason. The adherents want not only journalists to be activists, but demand the same of science, and even of mathematics.

They demand that every pursuit becomes activist, in aid of their particular cause.

For a perplexing exposition of the application of ‘critical pedagogy’ to mathematics, read this. Despite the fact that mathematics is a purely theoretical pursuit, the author believes that because we use ‘counting’ in social and political contexts, mathematics should have something to say about those social and political contexts.

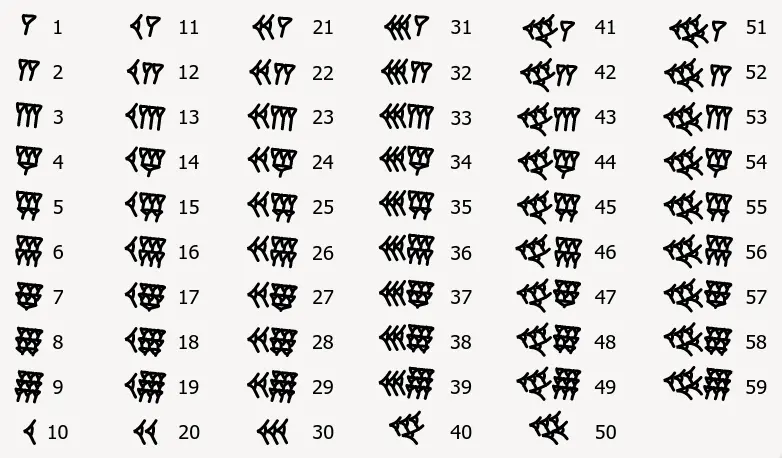

Consider this beauty: ‘Despite this most of us have only learned of our own and the Roman numerals. Our decision to exclude the Mayan, Babylonian, Chinese and Egyptian numeration systems among others is a political one.’

This was obviously written by someone who hasn’t the first clue about arithmetic, let alone mathematics. Actually, ‘our own’ numerals are Hindu-Arabic. They are not ‘our own’, and certainly not if your name is Dr. Lidia Gonzalez.

They were adopted in mathematics around the world because they were convenient, easy to use, and allowed symbolic manipulation that was cumbersome or impossible before.

Roman numerals are never used in mathematics, because like all the other number systems, they are inconvenient for both arithmetic and mathematical reasoning. It is arguable that the Roman Empire made few contributions to science and mathematics exactly because they used such a cumbersome system of numerals. There’s nothing political about it.

While the Babylonian number system was revolutionary for its time, try teaching a child those numerals, or explaining how (or why) to do arithmetic in base-60.

Not that bases other than ten are ignored in mathematics. They certainly have their uses and do come up in more advanced courses, although their notation can certainly be improved from cuneiform and Mayan script.

Inclusivity

Critical theorists argue that people are excluded from mathematics for some reason, yet the great strength of mathematics is that it transcends language, culture, nationality, skin-colour and politics. Mathematics is remarkably inclusive, being developed by people from all over the world, including Greece, Japan, China, Russia, India, Persia, Arabia, France, Germany, Britain, Italy and later, the United States. Its language is universal.

Dismissing the validity of objectivity, and elevating subjective experience as a replacement, is all done in pursuit of what critical theorists view as ‘social justice’.

Not everyone agrees with their particular conception of ‘social justice’, in which everything in society – up to and including mathematics – is analysed in Marxists terms on the basis of power relations between identitarian classes, including race, ability, gender identity, wealth, and anything else that can be used to distinguish between ‘oppressed’ and ‘oppressor’.

That dissent, however, is to be dealt with by means of censorship. Although they claim to seek a diversity of opinion, actually diverse opinions that differ from or disagree with their own class-warfare analysis are taboo. They dismiss audi alteram partem (hearing the other side, to use a legal phrase), as ‘false balance’ or ‘misleading bothsidesism’, as Downie puts it.

Of course, that does not mean that you have to tolerate lying, misinformation or disinformation, which is what the anti-objectivity crowd seems to fear.

Let’s just establish for a moment that lying happens all over the political spectrum. It is not the special preserve of the right, although admittedly, the right have elevated it to a high art.

In fact, much activist journalism has also courted inaccuracy, propaganda and outright lies. A prominent example is the New York Times’ 1619 Project, which the paper’s own Brett Stephens characterised as ‘a thesis in search of evidence, not the other way around’.

No, if facts contradict the statements of a given politician, then a good journalist presents both the statements, and those facts. The New York Times apologises for publishing the statement and promises never to do so again.

Irony

My objection to the subjectification of newsrooms is, perhaps, ironic, coming from someone who never really did mainstream reporting, and has written exclusively opinion for over 15 years. I’m certainly an activist, for free markets and individual liberty, and I have always been upfront about that fact.

However, in order for me to form sound opinions (which I hope I achieve more often than not), I am heavily reliant on primary reporting that is reliable, accurate, fair, nonpartisan, and a bona fide attempt to reflect the truth, as best as it can be apprehended.

That also means that I need to hear both sides of any story, and my research frequently proceeds from a first overview of an idea, to a review of opinions opposed to that idea.

It doesn’t help me to have one viewpoint declared to be truth, while disagreement is not only dismissed, but suppressed, as so-called fake news. Even if it is true, I need to be able to assess that for myself.

To navigate the world of political opinion it is often also necessary to at least be aware of, and try to understand, the views of people with whom you disagree.

When I sound dismissive of a particular point of view, it is only because I have spent a significant amount of time listening to it, and researching it, and trying to understand it.

I seek to understand what motivates socialists, for example, because without that, I cannot hope to convince them they’re wrong.

I need to understand why modern monetary theorists believe that they are right, before I can dismiss them as Magic Money Tree Theorists.

I am on a Telegram group run by a retired US military apparatchik who is pretty disgustingly pro-Russian, because I need to understand why both the Marxist left and the American alt-right think Russia was entirely justified in invading Ukraine, on the pretext of harbouring Nazis (which are far more numerous in Russia itself), and because they had the temerity to seek to join a defensive alliance that they obviously needed.

(After all, why South African right-wing pod bros who mistakenly believe themselves to be libertarian happen to share a position on that war with the ANC truly is a mystery.)

I need to understand what motivates anti-trans sentiment on the right and among the feminist left, as well as what motivates the movement against bigotry among many liberals.

I need to understand the religious right, since they are a massive political force that won’t simply disappear because the mainstream media gives them no airtime. On the contrary, suppressing them just gives them a persecution complex, which leads to conspiracy theories about all the money Bill Gates gave me to agitate for a tyrannical New World Order.

I need to understand what motivates xenophobia. When some populist politician says something reprehensible about foreign shop owners, or companies who employ migrants, I don’t want it suppressed by the media. On the contrary. I want it exposed.

Defending objectivity

Objectivity is an ideal. It does not exist in reality. Our experience of reality is strongly influenced by our social context, but that does not mean that journalistic (or indeed, scientific) attempts to represent reality are illegitimate.

Discarding objectivity as out-dated, however, is dangerous. We need hard-nosed, unemotional, detached reporting of fact. All of the opinion that populates our politics and socio-economic discourse ought to be based on fact, and not on only those facts that particular gate-keepers in the media want us to know.

It is a great irony that in seeking greater diversity of views, and in eliminating the gate-keeping of the ‘establishment’, editors like Downie threaten to achieve the exact opposite: suppressing a diversity of views and erecting new gate-keepers of ‘truth’.

The entire point of objectivity in reporting is that differing opinions and perspectives ought not to be suppressed, and that reporters ought not to act as gate-keepers of what they, subjectively, believe is right.

Call it ‘accuracy, fairness, nonpartisanship, accountability and the pursuit of truth’, then, if you will, but if journalism rejects objectivity in reporting, then the entire enterprise collapses upon itself.

All we’ll be left with is contesting opinions, with no way of telling reasonable opinions from unreasonable ones, and no way of determining – or at least trying to approach – the truth of any given matter.

Without objectivity, journalism is dead. Objectivity needs defending.

source:Objective journalism should be defended – Daily Friend

-

AuthorPosts

Viewing 1 post (of 1 total)

- You must be logged in to reply to this topic.